Napoleon III in Westminster,

erected 1867 and is the oldest surviving plaque

The Society of Arts’ earliest plaques had special patterned borders showing the Society’s name. Plaques were made of bronze, stone and lead, in square, round and rectangular forms, and were finished in brown, sage, terracotta or blue

In 1901 London County Council/LCC took over the scheme and formalised the selection criteria. The LCC’s first plaque commemorated historian Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1903, and then Charles Dickens’ house in Doughty St.

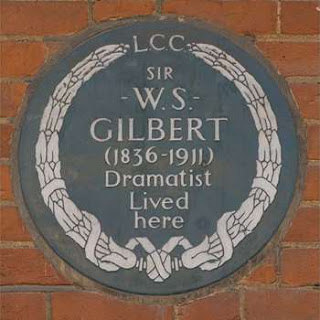

Known as the Indication of Houses of Historical Interest in London, the LCC continued to use the Minton factory, and they developed a highly decorative laurel wreath border with ribbon additions eg see the LCC plaque for librettist WS Gilbert in Sth Kensington. In the 35 years of Society of Arts management, it put up 35 plaques. Barely half of these survive, but John Keats, William Makepeace Thackeray and Edmund Burke’s did. ![]()

erected 1867 and is the oldest surviving plaque

A commemorative plaque scheme was first suggested to the House of Commons by William Ewart MP in 1863 and taken up by the Royal Society of Arts in London in 1866. They first commemorated the poet Lord Byron at his Cavendish Square home, but this house was demolished in 1889. So the plaque to Napoleon III in Westminster, erected 1867, is the earliest to have survived.

The Society of Arts’ earliest plaques had special patterned borders showing the Society’s name. Plaques were made of bronze, stone and lead, in square, round and rectangular forms, and were finished in brown, sage, terracotta or blue

In 1901 London County Council/LCC took over the scheme and formalised the selection criteria. The LCC’s first plaque commemorated historian Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1903, and then Charles Dickens’ house in Doughty St.

Known as the Indication of Houses of Historical Interest in London, the LCC continued to use the Minton factory, and they developed a highly decorative laurel wreath border with ribbon additions eg see the LCC plaque for librettist WS Gilbert in Sth Kensington. In the 35 years of Society of Arts management, it put up 35 plaques. Barely half of these survive, but John Keats, William Makepeace Thackeray and Edmund Burke’s did.

WS Gilbert, Plaque erected in 1929

Harrington Gardens, South Kensington, London,

The blue ceramic plaques became standard from 1921 because they stood out best in the London streetscape. They were made by Doulton from 1923-55, with a colourful raised wreath border. In 1938 the modern, simplified blue plaque was designed by a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. This omitted the laurel wreath and ribbon border, & simplified the overall layout, allowing for a bolder spacing and lettering arrangement. After WW2, plaques continued to be unveiled at a regular pace. By 1965, when the LCC was abolished, it had been responsible for creating nearly 250.

The LCC’s successor, Greater London Council/GLC, covered a wider area, now including Richmond and Croydon. From 1966-85, when the GLC was abolished, it had put up 262 plaques, honouring stars like Sylvia Pankhurst women’s campaigner, Mary Seacole Jamaican nurse and Crimean War heroine, and composer-conductor Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. From 1984 on, ceramicists Frank and Sue Ashworth made the blue plaques.

English Heritage took over the scheme in 1986 and didn’t change much. Except to be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed person must have died 20+ years previously. Its first plaque was in 1986, commemorating painter Oskar Kokoschka at Eyre Court in Finchley Rd, even though Kokoschka had been honoured with a CBE back in 1959. English Heritage’s recent plaques have ranged from Alan Turing to the guitarist-songwriter Jimi Hendrix. Since then English Heritage added 360+ plaques, bringing the total across London to 933.

In 2013–4 government cuts threatened the scheme, but its future was secured by large donations. English Heritage became a charity in 2015 and still manages the scheme.

Harrington Gardens, South Kensington, London,

The blue ceramic plaques became standard from 1921 because they stood out best in the London streetscape. They were made by Doulton from 1923-55, with a colourful raised wreath border. In 1938 the modern, simplified blue plaque was designed by a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. This omitted the laurel wreath and ribbon border, & simplified the overall layout, allowing for a bolder spacing and lettering arrangement. After WW2, plaques continued to be unveiled at a regular pace. By 1965, when the LCC was abolished, it had been responsible for creating nearly 250.

The LCC’s successor, Greater London Council/GLC, covered a wider area, now including Richmond and Croydon. From 1966-85, when the GLC was abolished, it had put up 262 plaques, honouring stars like Sylvia Pankhurst women’s campaigner, Mary Seacole Jamaican nurse and Crimean War heroine, and composer-conductor Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. From 1984 on, ceramicists Frank and Sue Ashworth made the blue plaques.

Alfred Hitchcock plaque

awarded in 1999

awarded in 1999

English Heritage took over the scheme in 1986 and didn’t change much. Except to be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed person must have died 20+ years previously. Its first plaque was in 1986, commemorating painter Oskar Kokoschka at Eyre Court in Finchley Rd, even though Kokoschka had been honoured with a CBE back in 1959. English Heritage’s recent plaques have ranged from Alan Turing to the guitarist-songwriter Jimi Hendrix. Since then English Heritage added 360+ plaques, bringing the total across London to 933.

In 2013–4 government cuts threatened the scheme, but its future was secured by large donations. English Heritage became a charity in 2015 and still manages the scheme.

Hendrix and Handel homes

museums on upper floors, 23-25 Brook St, Mayfair.

The most recent plaque honoured Isaiah Berlin, philosopher-political theorist-historian of ideas, whose Two Concepts of Liberty is an influential political text. Berlin’s plaque is at his childhood home in Holland Park.Isaiah Berlin, the newest plaque, 2022

33 Upper Addison Gardens, Holland Park

The most recent plaque honoured Isaiah Berlin, philosopher-political theorist-historian of ideas, whose Two Concepts of Liberty is an influential political text. Berlin’s plaque is at his childhood home in Holland Park.

33 Upper Addison Gardens, Holland Park

Is it too high for pedestrians to read?

I studied Australian history in primary school, but only British Empire, European and Russian history in high school & university. So when historians called for a Blue Plaque Programme in NSW years ago, I thoroughly agreed.

The home in which children’s author May Gibbs created the bush fairy tales of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie has now been recognised. Nutcote Cottage, Gibbs’ former studio on Sydney’s North Shore, is one of the first buildings in NSW to display a blue plaque modelled on London’s programme, and funded through Heritage NSW.

Premier Mr Perrottet said the Blue Plaque programme would successfully unlock the stories of NSW’s history, promoting the significance of key heritage places and people from all cultures. Artist Brett Whiteley and Indigenous champion Charles Perkins were two of the initial figures recognised by 700+ public nominations. In Apr 2022 NSW’s Heritage Minister Don Harwin announced 17 Blue Plaques, selected from 750 nominations made in Nov 2021 by community organisations and local councils. They’ll be installed across NSW later in 2022. Plaques will adorn the ex Registrar-General’s Building in Sydney designed by architect Walter Liberty Vernon, and heritage-listed Caroline Chisholm Cottage East Maitland, a hostel for homeless migrants.

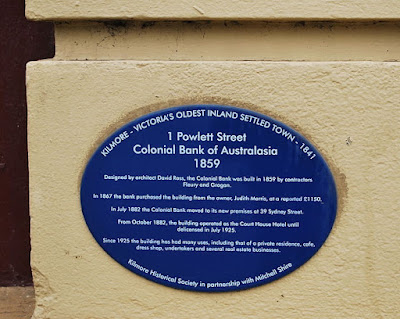

Blue plaques are also available to owners of sites listed in the Victorian Heritage Register. In 1999 the Mechanics Institute of Victoria Historical Plaques Programme planned to publicise the history of these Institutes across Victoria. The original Mechanics Institute was built in 1842 in Melbourne. The Athenaeum Building, with the statue of Athena on the parapet, was completed in 1886 to a design by architects Smith & Johnson, and is registered by the Heritage Council. Werribee Railway Station was completed in 1857 as part of the Geelong Melbourne Railway, Australia’s first country railway. It has retained its original walls, platform and cellar, and is registered. The Colonial Bank of Australasia building in Kilmore, later the Court House Hotel, is also easily identified now.

The Colonial Bank of Australasia building

Kilmore, Victoria

I studied Australian history in primary school, but only British Empire, European and Russian history in high school & university. So when historians called for a Blue Plaque Programme in NSW years ago, I thoroughly agreed.

The home in which children’s author May Gibbs created the bush fairy tales of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie has now been recognised. Nutcote Cottage, Gibbs’ former studio on Sydney’s North Shore, is one of the first buildings in NSW to display a blue plaque modelled on London’s programme, and funded through Heritage NSW.

Premier Mr Perrottet said the Blue Plaque programme would successfully unlock the stories of NSW’s history, promoting the significance of key heritage places and people from all cultures. Artist Brett Whiteley and Indigenous champion Charles Perkins were two of the initial figures recognised by 700+ public nominations. In Apr 2022 NSW’s Heritage Minister Don Harwin announced 17 Blue Plaques, selected from 750 nominations made in Nov 2021 by community organisations and local councils. They’ll be installed across NSW later in 2022. Plaques will adorn the ex Registrar-General’s Building in Sydney designed by architect Walter Liberty Vernon, and heritage-listed Caroline Chisholm Cottage East Maitland, a hostel for homeless migrants.

Blue plaques are also available to owners of sites listed in the Victorian Heritage Register. In 1999 the Mechanics Institute of Victoria Historical Plaques Programme planned to publicise the history of these Institutes across Victoria. The original Mechanics Institute was built in 1842 in Melbourne. The Athenaeum Building, with the statue of Athena on the parapet, was completed in 1886 to a design by architects Smith & Johnson, and is registered by the Heritage Council. Werribee Railway Station was completed in 1857 as part of the Geelong Melbourne Railway, Australia’s first country railway. It has retained its original walls, platform and cellar, and is registered. The Colonial Bank of Australasia building in Kilmore, later the Court House Hotel, is also easily identified now.

Kilmore, Victoria