During WW1 Richborough Camp was built on the River Stour, the starting point of a ferry service across the Channel for troops and munitions to France and Belgium. A railway was built from the main line to the banks of the Stour, so thousands of soldiers could be transported. But by late 1918, this British Army camp was left derelict.

The first men to arrive in Kitchener in 1939 had to rebuild

the old, derelict Richborough Camp from WW1.

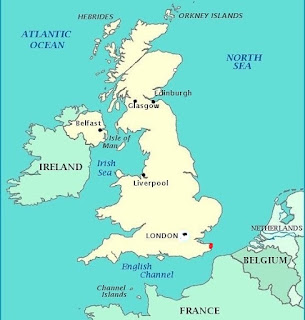

Location of Richborough/Kitchener Camp, Kent

across the Channel from France and Belgium

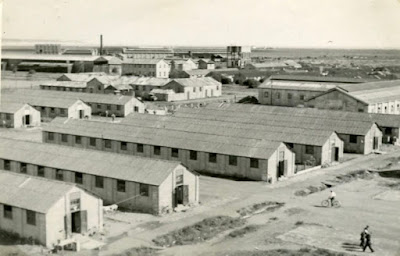

Richborough Camp and Port, Kent, in late 1918. So why was this camp rebuilt pre-WW2? By the late 1930s, the Council of German Jewry had been trying to organise a safe haven for citizens, especially once they were swamped with requests for help. In Kristallnacht Nov 1938, 25,000-30,000 Jewish men across Germany, Austria and Sudentenland were arrested & confined in Buchenwald, Dachau & Sachsenhausen concentration camps. They suffered starvation and torture, and hundreds died in the brutal conditions.

Ironically, release from the German camps depended on prisoners promising to LEAVE Germany asap! Other countries refused to take more refugees, so Kitchener Rescue began. Permission was given for the old camp to be rented by the Council of German Jewry, to provide a transit-camp refuge for Jewish working men. It was run by the Jewish aid organisations that organised the Kindertransport.

Until they had a safe haven, the men had to report weekly to a German police station; meanwhile they remained at risk of re-imprisonment and death. Thus the priority was to get these sons and husbands out of Germany urgently.

Ironically, release from the German camps depended on prisoners promising to LEAVE Germany asap! Other countries refused to take more refugees, so Kitchener Rescue began. Permission was given for the old camp to be rented by the Council of German Jewry, to provide a transit-camp refuge for Jewish working men. It was run by the Jewish aid organisations that organised the Kindertransport.

Until they had a safe haven, the men had to report weekly to a German police station; meanwhile they remained at risk of re-imprisonment and death. Thus the priority was to get these sons and husbands out of Germany urgently.

the old, derelict Richborough Camp from WW1.

Most men hoped that they’d have been able to gain employment somewhere and then bring their families from Germany to join them. Kitchener Camp never offered this opportunity because the refugees were only allowed temporary British residence visas and were required to move on elsewhere. To obtain a place at Kitchener, then, men had to show that they had a good chance of emigrating and finding work.

The sleeping huts and other facilities in Kitchener Camp were made ready

for 4,000 German Jewish men arriving in 1939

How did German Jewish men gain places at Kitchener? See the journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees/AJR which showed Werner Rosenstock had been employed at the Council of German Jewry in 1939, the only major Jewish German organisation still functioning post-Kristallnacht. He helped select as many men as possible from those with likely successful applications for transit visas. IF they were under 49 and had some kind of documentation promising entry to a foreign country, they could be selected from the mass of applicants freshly released from Nazi camps. NOT being selected could have been catastrophic.

Dormitory huts

Some men were selected for their ability to help rebuild Kitchener camp in Kent; showing their practical skills meant they had a good chance of being able to find work else where. Afterall taking Kitchener from a derelict site to habitable in a month, to house c4,000 people, was a huge task. The German men had to install doors, windows and panes, roofs and electric lights. After these repairs, each hut was divided into 2 sections, and 36 men slept in each.

Work was obligatory, and there was a lot to get through each day. Local farmers trained some men in skills for growing their own food, necessary both for their immediate situation and as a useful skill for employment later. There were also roads to be built, ditches to dig, drains to clear, and ongoing hut repairs. There was some time off from the labouring schedule, but it was stressful for those Germans who’d been used to a professional life. Others worked in the kitchens, preparing, cooking and cleaning 3 times a day. Remember that 3,500+ men were fed here daily, achieved by 400 men working in shifts.

Some men worked in the offices. And some taught classes since every man had to do English lessons, supplemented by locals from Sandwich. Rabbi Dr Werner van der Zyl led readings, discussions and services in Kitchener; he was aided by a cantor who’d been rescued by Kitchener’s transit scheme. Holy day celebrations were held in the camp tent in 1939 when services were held under wartime blackout conditions for c3,000 of the men.

Music became hugely significant and as more professional musicians arrived, a camp orchestra was formed. Such was the orchestra’s reputation that in August 1939, a live BBC broadcast of one of their concerts was planned.

Some men worked in the offices. And some taught classes since every man had to do English lessons, supplemented by locals from Sandwich. Rabbi Dr Werner van der Zyl led readings, discussions and services in Kitchener; he was aided by a cantor who’d been rescued by Kitchener’s transit scheme. Holy day celebrations were held in the camp tent in 1939 when services were held under wartime blackout conditions for c3,000 of the men.

Synagogue tent, Kitchener Camp

Used on high holy days

Used on high holy days

There was also a large contingent (c60) of dentists and doctors. So Kitchener camp had an isolation hospital unit, general hospital, First Aid unit and laboratory.

First aid station, Kitchener Camp

Musical presentation by Kitchener men

for camp residents and for visiting Sandwich families

For leisure activities, some men rode bikes along coastal paths or swam in the sea. On Saturdays they also had time allocated to play football. At night they were allowed out of the camp with a pass, although there was a night time curfew. Sandwich is a pretty, historic port-town, and in 1939 the historic homes and buildings in town were still appealing. A local store, Golden Crust Bakery, had furniture in the back, where they served meat pies and drinks. The owner was soon persuaded to sell European coffee, giving them somewhere hugely popular to go for Kaffee und Kuchen. Other men went to the Empire Cinema in Sandwich.

Despite the men being called Friendly Aliens, public opinion turned against German-speaking refugees after Dunkirk’s evacuation in May 1940 and the fall of France. Refugees had three choices: 1. serve in theBritish Army, 2. be interned or 3. be deported to Australia or Canada. Of the men on the infamous Dunera ship to Australia, 239 men had come from Kitchener.

Then Kitchener Camp was closed.

Thanks to Gerry Pearce, coordinator of the Berlin-Niederschoenhausen Project, for directing me to Kitchener Camp and for recommending Clare Ungerson’s book Four Thousand Lives (2014).