In the mid 1800s, Londoners didn’t have deep sewage toilets inside their homes. Citizens in the world’s biggest city used communal wells & pumps to get water needed for drinking, cooking and washing. Septic systems were so primitive that most buildings dumped untreated human and animal waste directly into the Thames River, or into open pits.

Cholera was an intestinal disease that caused death within hours of vomiting or diarrhoea appearing. The first British cholera cases were reported in 1831; from 1831-54, tens of thousands of people died of it.

London children bathed in, and drank from the same filthy streams used as slum sewers.

History Collection

Dr John Snow (1813–58), born into a working class family, believed that sewage-contaminated water caused cholera. Dr Snow published an article in 1849 outlining his theory, but doctors and scientists thought he was misguided; they stuck to their view that cholera was caused by stinking miasma. Dr Snow believed sewage dumped into the river or cesspools near town wells contaminated the water supply, and rapidly spread disease.

In Aug 1854 London’s Soho was hit by a terrible cholera outbreak, the third in London after 1832 and 1849. Dr Snow, who lived nearby, set out to prove his contaminated water theory. Where Cambridge St joined Broad St, there were 500+ cholera fatalities in 10 days. When he learned of the timing and extent of this outbreak, he zoomed in on the Broad St pump.

Dr John Snow (1813–58), born into a working class family, believed that sewage-contaminated water caused cholera. Dr Snow published an article in 1849 outlining his theory, but doctors and scientists thought he was misguided; they stuck to their view that cholera was caused by stinking miasma. Dr Snow believed sewage dumped into the river or cesspools near town wells contaminated the water supply, and rapidly spread disease.

In Aug 1854 London’s Soho was hit by a terrible cholera outbreak, the third in London after 1832 and 1849. Dr Snow, who lived nearby, set out to prove his contaminated water theory. Where Cambridge St joined Broad St, there were 500+ cholera fatalities in 10 days. When he learned of the timing and extent of this outbreak, he zoomed in on the Broad St pump.

Dr Snow tracked the data from hospital and public records, examining when the outbreak began and whether the victims drank Broad St pump water. Those who lived or worked near the pump were the most likely to use the pump and thus contract cholera. By using a geographical grid to chart deaths from the outbreak and investigating access to the pump water, Snow was recording proof that the pump was the epidemic source.

Snow also investigated groups of people who did NOT get cholera and asked whether they drank pump water or not. This would help him rule out other possible sources of the epidemic. A workhouse near Soho had 535 inmates but no cases of cholera, for example. This was because, he discovered, the workhouse had its own clean well!

And men who worked in a brewery on Broad St, making malt liquor, drank the liquor they made from the brewery’s own well. Not one of those men contracted cholera! Snow had proved that the cholera was not a problem in Soho EXCEPT among people who drank water from the Broad St pump.

In 1854, Dr Snow took his research results to the town officials and convinced them to remove the pump-handle, making it impossible to draw water. The officials were reluctant, but took the handle off as a trial, and found the cholera outbreak ended almost immediately. Eventually people who had left their homes and businesses in the Broad St area began to return.

John Snow and the Cholera Epidemic of 1854

by Charles River

Despite the success of Snow’s theory in curtailing Soho’s cholera epidemic, Board of Health reports downplayed Snow’s evidence as guesswork. Although Snow’s careful mapping became very important in locating cholera cases, public officials refused to clean up the drains and sewers.

For months after, Snow continued to track every case of cholera from the 1854 Soho outbreak and traced almost all of them back to the pump. But what he could NOT prove was where the contamination came from in the first place. Officials argued there was no way sewage from town pipes leaked into the pump and Snow couldn’t say whether it came from open sewers, drains under buildings, public pipes or cesspools.

Even a minister, Rev Henry Whitehead, challenged Dr Snow. Rev Whitehead was very troubled by the outbreak and its aftermath, but argued the outbreak was caused not by tainted water, but by God’s divine intervention. The Rev felt that many of the news reports were exaggerated and noted that even though the population of the area was decimated, there was no panic. Within a few weeks of the epidemic, Reverend Whitehead wrote his own account, entitled The Cholera in Berwick Street (1854). Not surprisingly, public officials took many more years before making improvements.

Dr Snow was not the last research-focused doctor who couldn’t convince the medical authorities of his discoveries. In the 1860s, Edinburgh surgeon Joseph Lister read a Louis Pasteur paper proving that fermentation was due to microorganisms. Lister was convinced that the same process accounted for wound sepsis, but surgeons wouldn’t use Lister’s antiseptic methods.

In 1865 when cholera returned to London, Rev Whitehead focused back on cholera. Dr Snow had already died, leaving Whitehead as the main authority on the earlier Broad St outbreak. Because of rising public alarm, Rev Whitehead re-published his work, acknowledging that cholera was a water-borne disease. In 1866, cholera broke out in the East London slums and spread by contaminated water to thousands.

Thankfully German physician Dr Robert Koch pursued the cause of cholera further in 1883 when he isolated bacterium vibrio cholerae. Dr Koch determined that cholera was not contagious from person to person, but was spread ONLY through unsanitary water, a late victory for Snow’s theory. Note that the C19th cholera epidemics in Europe and U.S ended after cities finally improved water supply sanitation.

The World Health Organisation suggests 78% of Third World countries’ citizens are still without clean water supplies, making some cholera outbreaks an ongoing concern. Now scientists call Dr Snow the pioneer of epidemiology/public health research. Much modern research still uses theories like his to track the sources and causes of many diseases. And now that bombed-out Mariupol faces a cholera epidemic, we understand that outbreaks are definitely an ongoing concern.

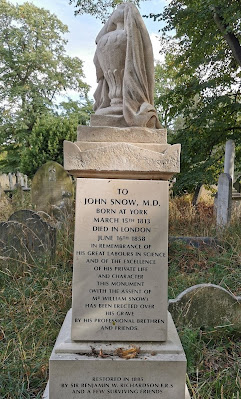

Dr J Snow's cemetery stone

Guest blogger: Dr Joe