Philip Goldstein Guston (1913-80)’s Ukrainian Jewish parents escaped pogrom violence so they moved to Canada from Odessa. Philip was born in Montreal then moved with his family to Los Angeles as a child. His parents had been brutally aware of Fascistic anti-Semitism at home, and Philip became aware of the regular Ku Klux Klan actions against Jews and blacks across California. Perhaps due to the earlier persecution, Philip’s father tragically hanged himself.

The Struggle Against Terror, mural, 1934-5 (top image)

Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish and Jules LangsnerMorelia, Mexico

In 1934 Guston went to Mexico with his artist friend Reuben Kadish & poet friend Jules Langsner where they were given space in Emperor Maximilian’s former summer palace. These artists created the impressive The Struggle Against Terror (1934-5), an anti-Fascist and pro-worker mural. The 3 colleagues, all Jewish sons of European parents, were clearly sensitive to racist policies in the USA and faced Red-baiting, witch-hunting and anti-Union activities of the KKK in response. In any case, criticism of the Catholic Church led to the mural being hidden away in the early 1940s.

In 1934 Guston went to Mexico with his artist friend Reuben Kadish & poet friend Jules Langsner where they were given space in Emperor Maximilian’s former summer palace. These artists created the impressive The Struggle Against Terror (1934-5), an anti-Fascist and pro-worker mural. The 3 colleagues, all Jewish sons of European parents, were clearly sensitive to racist policies in the USA and faced Red-baiting, witch-hunting and anti-Union activities of the KKK in response. In any case, criticism of the Catholic Church led to the mural being hidden away in the early 1940s.

Celebrated mainly for his abstract art, Philip Guston later decided to move into figurative painting that included the Ku Klux Klan motif. In this post, I am focusing solely on the later, anti-Fascist images of this politically-engaged artist.

Guston died in 1980 at 66. Below are some of the works to be shown .. well after his death.

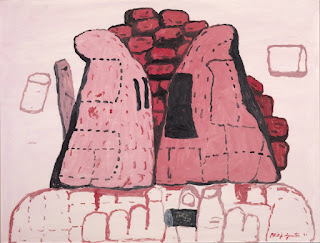

The Studio, 1969

Edge of Town, 1969

New York Times

Riding Around, 1969,

The GuardianThe decision to postpone the Guston show, which except for coronavirus would have begun earlier this year, caused conflict on both sides of the art world. So the retrospective was postponed, not for 3 months but for 4 years!! The four galleries said they’d wait until the powerful message of social and racial justice at the centre of Guston’s work could be more clearly understood. There was, they said, a risk that Guston’s messages could be misinterpreted and the resulting response could overshadow the totality of his legacy. And the 4 museums wanted to avoid painful experiences that the imagery could cause for viewers in 2020.

The directors recognised that the world was very different from what it had been in 2015, when they started the Guston project. The works that most ignited their concern were the white-hooded Ku Klux Klan figures. These white-hooded figures were images that the justice-focused, Jewish and left-wing artist had repeated from the early 1930s to his death. The directors felt it was necessary to reframe their programming, to step back and bring in new perspectives to shape how they presented Guston’s work to the public. That process will take time: until 2024.

Dawn, 1970,

Courtroom, 1970,

The Met

Cornered, 1971,

Tate

Art Daily reminded readers that art museums have, in the last three years, increasingly found themselves on the defensive for showing works that depicted racial violence. Some observers have protested the showing of work considered traumatising to communities scarred by that violence. Some work was removed from exhibitions. One painting was considered so sinister by the Ku Klux Klan that it was shot at and destroyed by Klan supporters.

But art academics told the Guardian that Guston’s work was exactly the kind of art that still needs to be discussed today. Guston’s work was deep; he had the foresight to see things as they were happening and his images are as poignant now as they had ever been. Art was not supposed to be a pretty picture; it was actually a reflection. So an exhibition organised several years ago, no matter how intelligent, must be reconsidered in light of what has changed. Thus the four museums seemed tone-deaf to what is happening in public discourse in 2020.

But art academics told the Guardian that Guston’s work was exactly the kind of art that still needs to be discussed today. Guston’s work was deep; he had the foresight to see things as they were happening and his images are as poignant now as they had ever been. Art was not supposed to be a pretty picture; it was actually a reflection. So an exhibition organised several years ago, no matter how intelligent, must be reconsidered in light of what has changed. Thus the four museums seemed tone-deaf to what is happening in public discourse in 2020.

Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer (b1943), said that she was saddened by the decision from the museums to postpone the exhibition. Her father had dared to unveil white culpability, the shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood. Her father had made a body of work that shocked the art world; he had violated the canon of what a noted abstract artist should be painting, at a time of doctrinaire art criticism! Furthermore he dared to hold a mirror to White America, exposing the Banality of Evil and the systemic racism the US was still struggling to confront today. In these works, cartoonish hooded figures evoked the Ku Klux Klan. They planned, plotted and rode around in cars smoking cigars. The viewer never saw their acts of hatred, never knew what was in their minds. But it was clear that they were us. Our denial, our concealment.

Musa believed this should be a time of reckoning & dialogue. The danger was not in looking at her father’s work, but in looking away.

Conclusion

Guston always considered his own KKK art to be about the pervasiveness of evil and white supremacy. A curator at the Modern Art Museum Fort Worth in Texas, who organised their Guston survey in 2003, concluded the case well: If the goal of the 2020 exhibition was to survey the late artist’s career in a contemporary context, it is ironic that if ever there was a poignant time to have these Guston images shown, it would be now!