Federation came to Australia on 1/1/1901. The Australian & New Zealand Army Corps were formed in Egypt in 1915 out of the 1st Australian Imperial Force/AIF and the 1st New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Soon after the birth of the nation, the Anzacs became best known for their bravery at the Battle of Gallipoli; for generations, it was commonly accepted that the Anzac tradition was inseparably identified with British Australians.

Yet in WW1, 1037 Russian men enlisted in the AIF, and most went on active service over seas. As the book Russian Anzacs in Australian History by Elena Govor (UNSW Press, 2005) says, they constituted the biggest non-Anglo national group in the AIF. The accompanying website has a page dedicated to the family- and service-history of each soldier.

During WW1, Russia was an important ally of the British Empire. So it made sense that Russian emigrants to Australia would be expected to return to Europe for the war. The tough Baltic seafaring peoples — Finns, Latvians, Estonians, Baltic Germans and Lithuanians were particularly well adapted to the armed forces. The remainder consisted of Ethnic Russians, Catholic and Jewish Poles, Ukrainians, Belarussians, Caucasus Ossetians, and Russian-born Western Europeans who were already flocking to Australia.

In 1916 the Australian official historian Charles Bean wrote that Pozières ridge in France is more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth. During the Pozières Battle, an entire section of the 9th Battalion was made up of Russians who became Australian soldiers.

We can see how the Anzac legend worked for someone who was different, had little English or spoke with a thick accent; how mateship was forged in battles, how suspicions ruined lives. Their stories were also stories of the unsung heroes of the war – the Australian women, those landladies who sent parcels to their Russian boys and the widows who married ex-servicemen post-war.

Only since the 1917 Revolution has Russia come to be seen as an enemy, rather than a friend of Australia. So we have to ask if each new generation of Australians reinvested the Anzac legend with its own anti-Russian perceptions. Could the many émigré communities be able to fully engage with the nation’s Anzac past? Only now, 100+ years after the Anzac legend started, the true diversity behind this national legend now includes Russia's heroic contribution.

During the centenary year of 1918, the Australian War Memorial is projecting names onto the façade of the Hall of Memory. Every night they recorded the names of all the fallen men, including the 162 fallen Russian Anzacs. Now the grandchildren of the Russians must preserve the memory of the soldiers. Film-maker Alex Spektor made a documentary, Anzacs from Russia, inspired by Elena Govor. Spektor explained that WW1 in Russia is remembered intensely and tragically, but do the Russians even know that their own citizens were fighting for Australian survival?

Yet in WW1, 1037 Russian men enlisted in the AIF, and most went on active service over seas. As the book Russian Anzacs in Australian History by Elena Govor (UNSW Press, 2005) says, they constituted the biggest non-Anglo national group in the AIF. The accompanying website has a page dedicated to the family- and service-history of each soldier.

During WW1, Russia was an important ally of the British Empire. So it made sense that Russian emigrants to Australia would be expected to return to Europe for the war. The tough Baltic seafaring peoples — Finns, Latvians, Estonians, Baltic Germans and Lithuanians were particularly well adapted to the armed forces. The remainder consisted of Ethnic Russians, Catholic and Jewish Poles, Ukrainians, Belarussians, Caucasus Ossetians, and Russian-born Western Europeans who were already flocking to Australia.

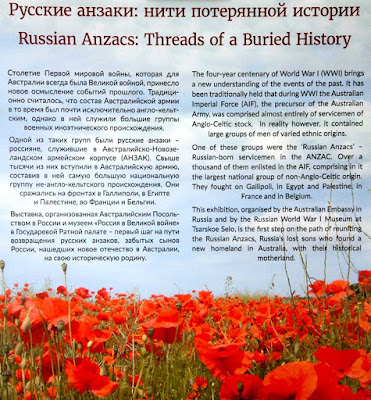

Australian Embassy exhibition "Russian Anzacs: Threads of a Buried History"

Tsarskoe Selo State Museum, Saint Petersburg

Russian émigrés had diverse reasons for enlisting early in the AIF: 1] some had fled their native land owing to ethnic or religious persecution in Eastern Europe, 2] others were labourers seeking quality jobs, 3] some had patriotic sentiments towards their new country, 4] many felt pressure exerted by the Russian consulate, 5] some to be with their mates or 6] the unemployed had few alternatives.

But their acceptance into the famous Anzac brotherhood was often hard-won. A lack of English was one stumbling block. In battles fought together, a comradeship with their Australian friends was forged. Major Eliazar Margolin grew up in the Jewish part of Belgorod, south of Moscow, near present-day Ukraine. While commanding the 16th Battalion at Gallipoli, Margolin and his thick Russian accent fought relentlessly for the lives of his boys. Plus he won official acknowledgement of his bravery with the Distinguished Service Order.

Later enlistment of Russian émigrés was due to the pressure exerted by the Russian government from Jan 1916 on; it demanded the conscription of all its subjects, at home or overseas. My grandfather, who arrived in Australia in Jan 1914 was desperate to go home to Russia; by the time war broke out in Sep 1914 he was prepared to lie about his age and to fake his late parents' signatures. He spoke little English, but he was very welcome in the Australian army because of his fluent Russian, Ukrainian, Yiddish, Hebrew, German and poor Polish. As did his brothers & first cousins.

Later enlistment of Russian émigrés was due to the pressure exerted by the Russian government from Jan 1916 on; it demanded the conscription of all its subjects, at home or overseas. My grandfather, who arrived in Australia in Jan 1914 was desperate to go home to Russia; by the time war broke out in Sep 1914 he was prepared to lie about his age and to fake his late parents' signatures. He spoke little English, but he was very welcome in the Australian army because of his fluent Russian, Ukrainian, Yiddish, Hebrew, German and poor Polish. As did his brothers & first cousins.

Michael Toberoff

Born Ukraine, 1890

Alec Cohen Croot

Born Latvia 1899

Pinchas Komesaroff

Born Ukraine, 1898

1 in 5 Russians died, a ratio similar to that of Australian soldiers across the board in WW1. But were Russians totally trusted in Australia? The decision by Australian soldiers not to question a fellow soldier because of some politicians in a distant country of origin was a relaxed attitude that was always cherished.

Some racism continued. Peter Chirvin from Sakhalin fought at Gallipoli and on the Western front for 4 years, being wounded twice. Risking his life, he carried the wounded from the battlefield, for which he was awarded the Military Medal. He returned to Australia on the troopship Anchises in 1919, and when soldiers on board ship started abusing him as a dreaded Russian-Orthodox Bolshie, their commanding officers did not intervene. Chirvin committed suicide on the ship, the last Australian victim of WW1.

Favst Leoshkevitch, on the other hand, was a seaman who learned English in the trenches from his Australian mates. After the war he told his son “what wonderful people our army people were just ordinary soldiers. When the revolution erupted in Russia nobody spoke to me about it and I thought that was wonderful”.

Integrating the Russian Anzacs into Australian life AFTER the war was no easy process either. Just like their Australian-born mates, these men rarely told their families about the horrors of the war. Some of them never spoke about their Russian past to their children, who grew up not speaking Russian with their fathers. This was the case for the daughter of Norman Myer, a lieutenant on the Western Front and heir to Australia's largest department store, Myer Emporium. Some of these men had burned all bridges with their homeland. A few returned home to Russia.

Some racism continued. Peter Chirvin from Sakhalin fought at Gallipoli and on the Western front for 4 years, being wounded twice. Risking his life, he carried the wounded from the battlefield, for which he was awarded the Military Medal. He returned to Australia on the troopship Anchises in 1919, and when soldiers on board ship started abusing him as a dreaded Russian-Orthodox Bolshie, their commanding officers did not intervene. Chirvin committed suicide on the ship, the last Australian victim of WW1.

Favst Leoshkevitch, on the other hand, was a seaman who learned English in the trenches from his Australian mates. After the war he told his son “what wonderful people our army people were just ordinary soldiers. When the revolution erupted in Russia nobody spoke to me about it and I thought that was wonderful”.

Integrating the Russian Anzacs into Australian life AFTER the war was no easy process either. Just like their Australian-born mates, these men rarely told their families about the horrors of the war. Some of them never spoke about their Russian past to their children, who grew up not speaking Russian with their fathers. This was the case for the daughter of Norman Myer, a lieutenant on the Western Front and heir to Australia's largest department store, Myer Emporium. Some of these men had burned all bridges with their homeland. A few returned home to Russia.

Shrine Reserve Melbourne

Only since the 1917 Revolution has Russia come to be seen as an enemy, rather than a friend of Australia. So we have to ask if each new generation of Australians reinvested the Anzac legend with its own anti-Russian perceptions. Could the many émigré communities be able to fully engage with the nation’s Anzac past? Only now, 100+ years after the Anzac legend started, the true diversity behind this national legend now includes Russia's heroic contribution.

During the centenary year of 1918, the Australian War Memorial is projecting names onto the façade of the Hall of Memory. Every night they recorded the names of all the fallen men, including the 162 fallen Russian Anzacs. Now the grandchildren of the Russians must preserve the memory of the soldiers. Film-maker Alex Spektor made a documentary, Anzacs from Russia, inspired by Elena Govor. Spektor explained that WW1 in Russia is remembered intensely and tragically, but do the Russians even know that their own citizens were fighting for Australian survival?