The White Man’s World by Bill Schwarz was published by Oxford University Press last year, but it doesn’t seemed to have arrived in our bookshops yet. So I will take some of the review written by the judges of this year’s Longman-History Today book awards, Juliet Gardiner and Jeremy Black, then add some thoughts of my own.

In his ambitious and provocative and accessible book, The White Man’s World, the first instalment of a trilogy, Memories of Empire, Bill Schwarz examined what the Empire meant to Britain’s idea of itself. He suggested that the loss of that Empire has inverted and reconfigured that meaning with profound social and cultural consequences which persist today. During the colonial period, the white man at the apogee of Empire represented the effortless superiority of the born-to-rule, of the authority implicit in muscular masculinity, subduing nature and natives. But after the colonial period, post-WW2 decolonisation produced confusion, a lack of confidence, a sense of a lost identity, a compass no longer set true. In this period it was the unappeased memories of Britain’s past that drove Britain’s new racial policies.

Enoch Powell (in and out of Parliament between 1950-1987) made his most vicious and racist Rivers of Blood speech in Birmingham in April 1968, in which he warned “real British citizens” of what he believed would be the consequences of continued unchecked immigration of “sham British citizens” from Commonwealth countries. And he practically wet his panties over the introduction of the Race Relations Act 1968, legislation prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of race, particularly in housing.

Schwarz was convinced that a perception of disorder and the high level of popular support for Enoch Powell following his big speech owed a considerable debt to the political-cultural effects of the end of Empire “at home” in the domestic society itself. He charted the deep-rooted construction of the understanding of Empire and its governance in order to comprehend the cultural and social effects of its loss on British society.

Schwarz’s project was to establish the link between an imperial past and the metropolitan present. And key to this was whiteness, bestowing an iconic status on the coloniser carrying the White Man’s Burden, of ruling and thus civilising the non-white natives. As it turned out, this authority would be inverted in the years of decolonisation back home.

Schwarz built his rich and detailed argument by devoting chapters to the so-called white man’s countries, the new colonies of South Africa, Rhodesia and Australia, set up at the start of the C20th. The whole was a story carried by a compelling range of individuals, colonial administrators, politicians, writers as varied as Rudyard Kipling, Charles Dickens, Henry James and Nadine Gordimer; and finishing with Rhodesians Roy Welensky and Ian Smith, last-ditch resisters both against black majority rule.

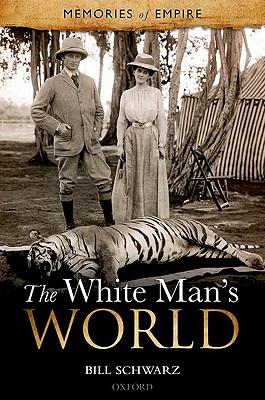

However despite the fact that there was a Raj-like photograph of a slain Indian tiger on the jacket, India – which was probably what most people thought of when they thought of Empire until the winds of change blew through Africa, figured marginally. Focus was placed instead on Australia, South Africa and Rhodesia.

The White Man’s World is an important book; a major contribution to interrogating the view that in general Empire had little impact on the British public – other than for trading and emigration opportunities – by showing how deeply formative its often imagined memory, symbols and myths are for our world today.

**

In my opinion, it was perfectly consistent for the British to mourn de-colonisation, a loss that produced a sense of a confused identity and a truly weakened power base. And it did not calm the sense of unease when historians indicated that the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire and every other power base in history had risen and risen, before falling off the face of the earth.

What was not consistent or rational were the newly emerging ideas about race. Consider how the colonial authorities converted the Empire into little versions of the motherland. The British rulers in India and every other British colony had changed almost every important aspect of life to suit British needs, viz:

the local legislation,

military command,

religion,

education system,

language

the economy

criminal and civil courts

civic and domestic architecture

imports and exports

health care

and every other thing.

The consequences were clear. Of course citizens in the colonies were going to have to become British, to survive and flourish. To respond that citizens in these colonies were of a different race and therefore not truly British smacks of late-found hypocrisy.

If the coloniser’s role was a] carrying the White Man’s Burden, b] ruling and c] civilising the non-white natives, then Britain was very successful. Yet one of the main themes both in Powell's speech, and in reactions to it, was the idea that post-WW2 the British nation was under threat of destruction: stabbed in the back by a treacherous ruling elite - Macmillan, Wilson, Heath, Major - betraying race and nation.

How could the coloniser’s role be both very successful and moral in the colonies before 1950 and yet viciously destructive of Britain and immoral after 1950? It was a malign fantasy, but one with a powerful collective appeal.

So modern ideas of race DID shape the collective imaginings, political rhetoric and cultural workings of national life, of Britishness. Instead of ideas about race dying with decolonisation as they should have done, they perversely came alive again, recalling the Empire as some sort of lost racial Utopia. Powellism was largely about the reworking of these experiences within Britain.

I would probably have noted how unlikely this post-colonial view sounded … except for the fact that spouse and I lived in Britain during the early and middle 1970s. The popular response to Powell was surprisingly (to me) passionate! It really did illuminate deeper currents of social change, the loss of empire and hidden anxieties about what it meant to be white.

In his ambitious and provocative and accessible book, The White Man’s World, the first instalment of a trilogy, Memories of Empire, Bill Schwarz examined what the Empire meant to Britain’s idea of itself. He suggested that the loss of that Empire has inverted and reconfigured that meaning with profound social and cultural consequences which persist today. During the colonial period, the white man at the apogee of Empire represented the effortless superiority of the born-to-rule, of the authority implicit in muscular masculinity, subduing nature and natives. But after the colonial period, post-WW2 decolonisation produced confusion, a lack of confidence, a sense of a lost identity, a compass no longer set true. In this period it was the unappeased memories of Britain’s past that drove Britain’s new racial policies.

Enoch Powell (in and out of Parliament between 1950-1987) made his most vicious and racist Rivers of Blood speech in Birmingham in April 1968, in which he warned “real British citizens” of what he believed would be the consequences of continued unchecked immigration of “sham British citizens” from Commonwealth countries. And he practically wet his panties over the introduction of the Race Relations Act 1968, legislation prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of race, particularly in housing.

Schwarz was convinced that a perception of disorder and the high level of popular support for Enoch Powell following his big speech owed a considerable debt to the political-cultural effects of the end of Empire “at home” in the domestic society itself. He charted the deep-rooted construction of the understanding of Empire and its governance in order to comprehend the cultural and social effects of its loss on British society.

Schwarz’s project was to establish the link between an imperial past and the metropolitan present. And key to this was whiteness, bestowing an iconic status on the coloniser carrying the White Man’s Burden, of ruling and thus civilising the non-white natives. As it turned out, this authority would be inverted in the years of decolonisation back home.

Schwarz built his rich and detailed argument by devoting chapters to the so-called white man’s countries, the new colonies of South Africa, Rhodesia and Australia, set up at the start of the C20th. The whole was a story carried by a compelling range of individuals, colonial administrators, politicians, writers as varied as Rudyard Kipling, Charles Dickens, Henry James and Nadine Gordimer; and finishing with Rhodesians Roy Welensky and Ian Smith, last-ditch resisters both against black majority rule.

However despite the fact that there was a Raj-like photograph of a slain Indian tiger on the jacket, India – which was probably what most people thought of when they thought of Empire until the winds of change blew through Africa, figured marginally. Focus was placed instead on Australia, South Africa and Rhodesia.

The White Man’s World is an important book; a major contribution to interrogating the view that in general Empire had little impact on the British public – other than for trading and emigration opportunities – by showing how deeply formative its often imagined memory, symbols and myths are for our world today.

**

In my opinion, it was perfectly consistent for the British to mourn de-colonisation, a loss that produced a sense of a confused identity and a truly weakened power base. And it did not calm the sense of unease when historians indicated that the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire and every other power base in history had risen and risen, before falling off the face of the earth.

What was not consistent or rational were the newly emerging ideas about race. Consider how the colonial authorities converted the Empire into little versions of the motherland. The British rulers in India and every other British colony had changed almost every important aspect of life to suit British needs, viz:

the local legislation,

military command,

religion,

education system,

language

the economy

criminal and civil courts

civic and domestic architecture

imports and exports

health care

and every other thing.

The consequences were clear. Of course citizens in the colonies were going to have to become British, to survive and flourish. To respond that citizens in these colonies were of a different race and therefore not truly British smacks of late-found hypocrisy.

If the coloniser’s role was a] carrying the White Man’s Burden, b] ruling and c] civilising the non-white natives, then Britain was very successful. Yet one of the main themes both in Powell's speech, and in reactions to it, was the idea that post-WW2 the British nation was under threat of destruction: stabbed in the back by a treacherous ruling elite - Macmillan, Wilson, Heath, Major - betraying race and nation.

How could the coloniser’s role be both very successful and moral in the colonies before 1950 and yet viciously destructive of Britain and immoral after 1950? It was a malign fantasy, but one with a powerful collective appeal.

So modern ideas of race DID shape the collective imaginings, political rhetoric and cultural workings of national life, of Britishness. Instead of ideas about race dying with decolonisation as they should have done, they perversely came alive again, recalling the Empire as some sort of lost racial Utopia. Powellism was largely about the reworking of these experiences within Britain.

I would probably have noted how unlikely this post-colonial view sounded … except for the fact that spouse and I lived in Britain during the early and middle 1970s. The popular response to Powell was surprisingly (to me) passionate! It really did illuminate deeper currents of social change, the loss of empire and hidden anxieties about what it meant to be white.