50,000 Jews lived in Kishinev (now Ukraine) in 1900, 46% of the total population. Kishinev was the 5th largest Jewish city in the Russian Empire city after Warsaw, Odessa, Lodz and Vilna. Thanks to the book, Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History (Steven Zipperstein, 2018) and to my grandfather.

Rumours of attacks surfaced before Easter each year in Kishinev. Accusations of ritual murder in Pavel Krushevan’s anti-Semitic newspaper, Bessarabets, remained ugly; there were rumours of menacing anti-Jewish meetings held in the back room of a Kishinev tavern, and leaflets calling for the beating of Jews were left in bars and cheap restaurants. By then Bessarabets had launched a semi-secret, anti-Semitic society.

Against this backdrop, Jewish anxieties were heightened. Jewish shop owners took home bank records, receipts and financial documents for safekeeping. Employees were told that shops could stay shut after the Passover festival.

Heartbroken fathers claimed their children's bodies

By late morning, well-dressed Christian families sauntered out of church and into the cluttered city square. In previous years Easter had celebrated with a merry-go-round, but officials seeking to dampen holiday revelry shut it down in 1903. Some Jews gravitated to the square, despite warnings that Jews should go directly home after Passover.

Then groups of young boys started roughing Jews up. People jostled in a sparsely policed public square, lined with Jewish-owned shops. The taunting continued, but most assumed it was only a harmless prank. When adults started tossing rocks at Jewish shop windows, police intervened but they caught only a handful of thugs.

As the Easter crowd grew, some became very drunk. Russian Orthodox students in uniform came from the local seminary, inciting the crowds. And workers sporting festive red shirts were rabble-rousers close to Pavel Krushevan.

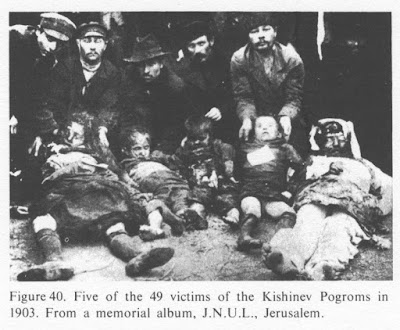

This was the pogrom that took place in Kishinev, then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate, in mid April 1903. In the First Kishinev pogrom, 49 Jews were murdered, many Jewish women were raped, 1,500 homes were burned and 600 shops were destroyed.

Jewish-owned shops in the central square were ransacked. Liquor shops were targeted first. Tobacco shops were ransacked next. Then the rioters arrived at the New Market, one k from the city centre. They stole clothes off the racks of Jewish shops and walked through the city streets with the goods. Unwanted merchandise was piled onto roads. The rioters thought to be most fierce were Moldovans, hailing from the adjacent villages west of the Ukraine. Many arrived with wagons to carry away the contents of Jewish shops.

But as no more than 2-3 dozen people were responsible for the rioting, they were written off as rowdy drunks. However by 4 pm, the seminarians guided the mob to Jewish homes to destroy them. Cries of “Death to Jews!” and “Jews drink Christian blood” could be heard. Jews begged the police for help but were told that the mob was beyond police control.

Christians scrawled crosses on the windows of their homes to protect themselves from attack, and doctors helping wounded Jews wore crosses on their clothes. Meat slabs found cooking in a Jewish shop owner’s home/shop were shown to rioters as the “remains of a Christian child”.

Public transport (trams) across town was infrequent so the rioters had to pillage mostly by foot. Yet two-thirds of Kishinev had been affected by violence; entire streets were largely levelled. Late on the first night, Jewish merchants gathered their neighbours together and distributed iron bars and wooden clubs, to fight the next day if attacked by adults. Those with money fled to nearby hotels, or to board trains for Kiev, Odessa or Vienna.

Homes destroyed and furniture thrown into the courtyard

The next morning 150 Jews converged on Governor General Raaben’s offices. A small delegation could meet him and were assured that order would immediately be restored. Alas the Governor General was believed.

Distant Lower Kishinev, built on hills above Byk River, was dotted with tiny shops, synagogues and houses built around courtyards crammed with very large Jewish families and Moldovan Christian families. Neighbours had previously been friendly, or at least neutral. So it was more typical than elsewhere in Kishinev for Christian families to take dangerous risks to save their Jewish neighbours.

Nonetheless on Day 2, violence in Lower Kishinev was concentrated in inter-connecting alleyways, packed with flimsy structures that collapsed under attack. The mob engulfing Lower Kishinev included villagers from outside the city, driving wagons in to steal Jewish goods. In poor synagogues, holy Torah scrolls were desecrated. Jewish reports focused attention on Lower Kishinev’s poor; it was a catastrophe of the many poor, and not of the fewer rich.

Corpses were tossed onto the street, and lay there for hours until cleared by the army. Yet by the end of the second day, only 900 rioters had been arrested. Even two months later, rough boards covered the broken windows, shattered doors and damaged roofs of many houses, and dried blood was everywhere.

City newspaper and journal articles soon downplayed the role played by seminary students. And Krushevan’s anti-Semitic newspaper was relegated to a minor role. The story was reduced to a “few hours of intense violence that erupted just hours before the pogrom was ended”.

The Second Kishinev Pogrom took place in mid October 1905. This time the riots began as political protests against the Tsar, but turned into an anti-Semitic attack when another 19 Jews were killed and dozens injured. Jewish self-defence leagues, organised after the first pogrom, stopped some of the violence, but not totally. And 600 further pogroms swept the Russian Empire after the October Manifesto of 1905.

With all those murders and rapes, only two Christian men were sentenced to 5-7 years and 22 were sentenced for 1-2 years. Hundreds of thousands of Russian Jews left for Palestine or The West.

Chaim Bialik was sent by Odessa’s Jewish Historical Commission to interview pogrom survivors and report. His famous poem was called "The City of Slaughter". In Ephraim Moses Lilien work “To the Martyrs of Kishinev”, the Jews’ martyrdom became a medieval-like tale, wrapped in a traditional prayer shawl. Israel Zangwill wrote the post-Kishinev play “The Melting Pot” in 1908.

Map of Novorossiya/New Russia, 1900

My family lived near Odessa, Simferopol (Crimea) and Berdiansk (B marked on Azov Sea)

Rumours of attacks surfaced before Easter each year in Kishinev. Accusations of ritual murder in Pavel Krushevan’s anti-Semitic newspaper, Bessarabets, remained ugly; there were rumours of menacing anti-Jewish meetings held in the back room of a Kishinev tavern, and leaflets calling for the beating of Jews were left in bars and cheap restaurants. By then Bessarabets had launched a semi-secret, anti-Semitic society.

Against this backdrop, Jewish anxieties were heightened. Jewish shop owners took home bank records, receipts and financial documents for safekeeping. Employees were told that shops could stay shut after the Passover festival.

Heartbroken fathers claimed their children's bodies

By late morning, well-dressed Christian families sauntered out of church and into the cluttered city square. In previous years Easter had celebrated with a merry-go-round, but officials seeking to dampen holiday revelry shut it down in 1903. Some Jews gravitated to the square, despite warnings that Jews should go directly home after Passover.

Then groups of young boys started roughing Jews up. People jostled in a sparsely policed public square, lined with Jewish-owned shops. The taunting continued, but most assumed it was only a harmless prank. When adults started tossing rocks at Jewish shop windows, police intervened but they caught only a handful of thugs.

As the Easter crowd grew, some became very drunk. Russian Orthodox students in uniform came from the local seminary, inciting the crowds. And workers sporting festive red shirts were rabble-rousers close to Pavel Krushevan.

This was the pogrom that took place in Kishinev, then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate, in mid April 1903. In the First Kishinev pogrom, 49 Jews were murdered, many Jewish women were raped, 1,500 homes were burned and 600 shops were destroyed.

Jewish-owned shops in the central square were ransacked. Liquor shops were targeted first. Tobacco shops were ransacked next. Then the rioters arrived at the New Market, one k from the city centre. They stole clothes off the racks of Jewish shops and walked through the city streets with the goods. Unwanted merchandise was piled onto roads. The rioters thought to be most fierce were Moldovans, hailing from the adjacent villages west of the Ukraine. Many arrived with wagons to carry away the contents of Jewish shops.

But as no more than 2-3 dozen people were responsible for the rioting, they were written off as rowdy drunks. However by 4 pm, the seminarians guided the mob to Jewish homes to destroy them. Cries of “Death to Jews!” and “Jews drink Christian blood” could be heard. Jews begged the police for help but were told that the mob was beyond police control.

Christians scrawled crosses on the windows of their homes to protect themselves from attack, and doctors helping wounded Jews wore crosses on their clothes. Meat slabs found cooking in a Jewish shop owner’s home/shop were shown to rioters as the “remains of a Christian child”.

Public transport (trams) across town was infrequent so the rioters had to pillage mostly by foot. Yet two-thirds of Kishinev had been affected by violence; entire streets were largely levelled. Late on the first night, Jewish merchants gathered their neighbours together and distributed iron bars and wooden clubs, to fight the next day if attacked by adults. Those with money fled to nearby hotels, or to board trains for Kiev, Odessa or Vienna.

Homes destroyed and furniture thrown into the courtyard

The next morning 150 Jews converged on Governor General Raaben’s offices. A small delegation could meet him and were assured that order would immediately be restored. Alas the Governor General was believed.

Distant Lower Kishinev, built on hills above Byk River, was dotted with tiny shops, synagogues and houses built around courtyards crammed with very large Jewish families and Moldovan Christian families. Neighbours had previously been friendly, or at least neutral. So it was more typical than elsewhere in Kishinev for Christian families to take dangerous risks to save their Jewish neighbours.

Nonetheless on Day 2, violence in Lower Kishinev was concentrated in inter-connecting alleyways, packed with flimsy structures that collapsed under attack. The mob engulfing Lower Kishinev included villagers from outside the city, driving wagons in to steal Jewish goods. In poor synagogues, holy Torah scrolls were desecrated. Jewish reports focused attention on Lower Kishinev’s poor; it was a catastrophe of the many poor, and not of the fewer rich.

Corpses were tossed onto the street, and lay there for hours until cleared by the army. Yet by the end of the second day, only 900 rioters had been arrested. Even two months later, rough boards covered the broken windows, shattered doors and damaged roofs of many houses, and dried blood was everywhere.

City newspaper and journal articles soon downplayed the role played by seminary students. And Krushevan’s anti-Semitic newspaper was relegated to a minor role. The story was reduced to a “few hours of intense violence that erupted just hours before the pogrom was ended”.

The Second Kishinev Pogrom took place in mid October 1905. This time the riots began as political protests against the Tsar, but turned into an anti-Semitic attack when another 19 Jews were killed and dozens injured. Jewish self-defence leagues, organised after the first pogrom, stopped some of the violence, but not totally. And 600 further pogroms swept the Russian Empire after the October Manifesto of 1905.

With all those murders and rapes, only two Christian men were sentenced to 5-7 years and 22 were sentenced for 1-2 years. Hundreds of thousands of Russian Jews left for Palestine or The West.

Chaim Bialik was sent by Odessa’s Jewish Historical Commission to interview pogrom survivors and report. His famous poem was called "The City of Slaughter". In Ephraim Moses Lilien work “To the Martyrs of Kishinev”, the Jews’ martyrdom became a medieval-like tale, wrapped in a traditional prayer shawl. Israel Zangwill wrote the post-Kishinev play “The Melting Pot” in 1908.

Map of Novorossiya/New Russia, 1900

My family lived near Odessa, Simferopol (Crimea) and Berdiansk (B marked on Azov Sea)