Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, Netherlands etc had booming colonial empires, often after long and brutal struggles against local citizens. By the late 19th century, Germany also wanted colonies.

We need to start with Germany's unification in 1871. Although the German Empire went on to become a European colonial power until the end of WW1, it might be difficult for the modern historian to see how colonial power entered public consciousness. Certainly not from Otto von Bismarck and the politicians in the Reichstag who felt they had enough

problems to deal with, inside the new German nation.

However it must be noted that there were many geographical associations and colonial societies in Germany. And there were many German citizens who moved to the colonies, temporarily or for the long term: missionaries, civil servants, military people, settlers and merchants.

In 1884 Bismarck reluctantly changed his mind. In order to protect trade, to safeguard raw materials and export markets and to build capital investment, he approved the acquisition of colonies by the German Empire.

As a straggler in the race for colonies, Germany had to agree to four less-than-desirable Protectorates.

A) In South West Africa, they colonised Namibia (1884-1918).

B) In East Africa, the Germans colonised the nations now called Cameroon, Togo, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, Mozambique and Rwanda (1891-1918).

C) To protect German trading interests in the Pacific and to take advantage of British failures, the German Government annexed north eastern New Guinea in 1884. The Marshall and the Solomon Islands were annexed in 1885. The Germans took over Nauru, then annexed Samoa to acquire forced labour for its plantations.

D) In China, Qingdao Treaty Port became the German bay concession of Tsingtau, leased by the Qing Dynasty. From 1898-1914, it was the centre for German commercial development in China and a base for the Imperial German Navy.

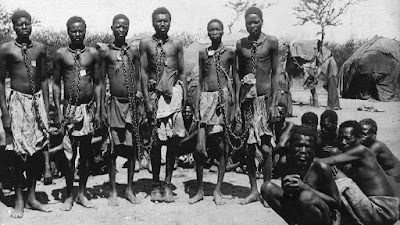

German military forces had to battle against many angry marches, to lock up or execute local trouble makers. Perhaps it was because Germany became involved in empire building much later than the other Europeans, and were therefore less experienced. Africans resisted the annexation of their territories, which led to violent colonial wars. Genocide in Namibia was infamous as one of the first examples of genocide in the C20th. Between 1904-05, tens of thousands of rebelling Herero and Namaqua died when the German army destroyed supplies of food and water. Afterwards, the colonising army drove refugees into the Namib Desert.

We need to start with Germany's unification in 1871. Although the German Empire went on to become a European colonial power until the end of WW1, it might be difficult for the modern historian to see how colonial power entered public consciousness. Certainly not from Otto von Bismarck and the politicians in the Reichstag who felt they had enough

problems to deal with, inside the new German nation.

However it must be noted that there were many geographical associations and colonial societies in Germany. And there were many German citizens who moved to the colonies, temporarily or for the long term: missionaries, civil servants, military people, settlers and merchants.

In 1884 Bismarck reluctantly changed his mind. In order to protect trade, to safeguard raw materials and export markets and to build capital investment, he approved the acquisition of colonies by the German Empire.

Plus Pacific islands and Chinese concessions in red

As a straggler in the race for colonies, Germany had to agree to four less-than-desirable Protectorates.

A) In South West Africa, they colonised Namibia (1884-1918).

B) In East Africa, the Germans colonised the nations now called Cameroon, Togo, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, Mozambique and Rwanda (1891-1918).

C) To protect German trading interests in the Pacific and to take advantage of British failures, the German Government annexed north eastern New Guinea in 1884. The Marshall and the Solomon Islands were annexed in 1885. The Germans took over Nauru, then annexed Samoa to acquire forced labour for its plantations.

D) In China, Qingdao Treaty Port became the German bay concession of Tsingtau, leased by the Qing Dynasty. From 1898-1914, it was the centre for German commercial development in China and a base for the Imperial German Navy.

German military forces had to battle against many angry marches, to lock up or execute local trouble makers. Perhaps it was because Germany became involved in empire building much later than the other Europeans, and were therefore less experienced. Africans resisted the annexation of their territories, which led to violent colonial wars. Genocide in Namibia was infamous as one of the first examples of genocide in the C20th. Between 1904-05, tens of thousands of rebelling Herero and Namaqua died when the German army destroyed supplies of food and water. Afterwards, the colonising army drove refugees into the Namib Desert.

Germany committed its first mass deaths in Namibia against the Namas and the Hereros, from 1904 to 1907, often in camps.

In Tanzania in German East Africa, the 1905 Maji-Maji War was another devastating event for the local population. The Maji Majis had to work in labour gangs to build roads and grow cotton, but they died from largely from German-organised famine.

Even in times of peace, the military forces employed the Maxim machine gun to reinforce their rule and bring home the superiority of the Europeans to the colonised peoples. The machine gun was sometimes used to decimate whole groves of trees in a short period of time to engender fear, or destroy food.

These genocides were a source of tension between the German Empire and other European powers, especially Britain and France. This was even though a] Germany did not have the military resources to seriously compete and v] Britain and France had their own colonial wars and their own brutal colonial histories.

A conference was organised by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, with representatives of 14 nations, but no Africans were invited. The General Act of the Berlin Conference of 1884-5 formalised the Scramble for Africa, and eliminated most existing forms of African self-rule. Germany was placing colonialism in its pan-European context, and publicising its sudden emergence as an imperial power.

German colonial efforts, despite being limited, did not create a happy time in world history. So it did not surprise historians that early in WWI, most of Germany’s African and Pacific colonies were occupied by other European colonial powers. Only in German East Africa did the Generals and African mercenaries persevere until the end of the war.

Perhaps because of its tradition of expansion within Europe, Germany's renewed attempt to conquer Europe in WWI resulted in loss of its overseas possessions. Post-WW1 Germany was stripped of all its colonies under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The confiscated territories were distributed to the victors, under the new system of mandates set up by the League of Nations.

Thus the German colonial empire ended. Yet colonial consciousness did not disappear. Nazi Germany’s attempt to acquire new European “colonies” before and during WW2 started with the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia. Then Germany wanted parts of Poland, Ukraine, Russia and Baltic states. Undoubtedly there was a legitimate concern for the millions of ethnic Germans who lived there, but that would have led to the unification of Greater Germany, not colonisation of unrelated European nations.

Even in times of peace, the military forces employed the Maxim machine gun to reinforce their rule and bring home the superiority of the Europeans to the colonised peoples. The machine gun was sometimes used to decimate whole groves of trees in a short period of time to engender fear, or destroy food.

These genocides were a source of tension between the German Empire and other European powers, especially Britain and France. This was even though a] Germany did not have the military resources to seriously compete and v] Britain and France had their own colonial wars and their own brutal colonial histories.

A conference was organised by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, with representatives of 14 nations, but no Africans were invited. The General Act of the Berlin Conference of 1884-5 formalised the Scramble for Africa, and eliminated most existing forms of African self-rule. Germany was placing colonialism in its pan-European context, and publicising its sudden emergence as an imperial power.

German colonial efforts, despite being limited, did not create a happy time in world history. So it did not surprise historians that early in WWI, most of Germany’s African and Pacific colonies were occupied by other European colonial powers. Only in German East Africa did the Generals and African mercenaries persevere until the end of the war.

Perhaps because of its tradition of expansion within Europe, Germany's renewed attempt to conquer Europe in WWI resulted in loss of its overseas possessions. Post-WW1 Germany was stripped of all its colonies under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The confiscated territories were distributed to the victors, under the new system of mandates set up by the League of Nations.

Thus the German colonial empire ended. Yet colonial consciousness did not disappear. Nazi Germany’s attempt to acquire new European “colonies” before and during WW2 started with the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia. Then Germany wanted parts of Poland, Ukraine, Russia and Baltic states. Undoubtedly there was a legitimate concern for the millions of ethnic Germans who lived there, but that would have led to the unification of Greater Germany, not colonisation of unrelated European nations.

in khaki uniforms and helmets

For the first time Berlin's Deutsches Historisches Museum has focused on German colonialism in an exhibition called German Colonialism Fragments Past and Present (Oct 2016-May 2017).

Displays dealt with German colonialism via paintings, graphics, everyday objects, posters, documents, photographs, colonial wares, toys and travel reports from Germans and locals. One example. European civil servants and military travellers from all the colonial powers wore tropical helmets made of pith or cork. Used extensively across all the tropical colonies, the helmets offered protection against sun and rain for Imperial German Officials. The helmet became a fixture of the colonial dress code and a sign of membership of the racially-defined rulers.

The exhibition examined the motives of the German missionaries, administrators, military forces, settlers and merchants, as well as the interests of the colonised people. And it examined whether the perspectives of the colonised peoples were included in the historical tradition.

The exhibition published by an excellent booklet in German and English. From this catalogue, I was most interested in the underlying ideology of colonialism, worldwide political rivalry with other colonial powers, and the pursuit of economic power in the 19th and early C20th. The discussion of German domination, with its violence, crushing of rebellions and genocide, was harsher. Nonetheless the exhibition did inform current debates about the recognition of genocides.

For the first time Berlin's Deutsches Historisches Museum has focused on German colonialism in an exhibition called German Colonialism Fragments Past and Present (Oct 2016-May 2017).

Displays dealt with German colonialism via paintings, graphics, everyday objects, posters, documents, photographs, colonial wares, toys and travel reports from Germans and locals. One example. European civil servants and military travellers from all the colonial powers wore tropical helmets made of pith or cork. Used extensively across all the tropical colonies, the helmets offered protection against sun and rain for Imperial German Officials. The helmet became a fixture of the colonial dress code and a sign of membership of the racially-defined rulers.

The exhibition examined the motives of the German missionaries, administrators, military forces, settlers and merchants, as well as the interests of the colonised people. And it examined whether the perspectives of the colonised peoples were included in the historical tradition.

The exhibition published by an excellent booklet in German and English. From this catalogue, I was most interested in the underlying ideology of colonialism, worldwide political rivalry with other colonial powers, and the pursuit of economic power in the 19th and early C20th. The discussion of German domination, with its violence, crushing of rebellions and genocide, was harsher. Nonetheless the exhibition did inform current debates about the recognition of genocides.