Art historians often cite rabbinical rulings against all Jewish art in the Middle Ages. But any such restrictions were limited to the geographic community where each ruling was given!! And in any case, they were no longer applicable by the C19th. Even better, national art schools and academies formally opened their doors to Jewish students in the C19th, in Britain, Italy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Romania etc.

A work from this later era was Rabbi with A Young Student. Kaufmann reflected the pride he felt for the traditional religious life. The teacher displayed a sense of solemnity and perhaps wisdom. The young student was caught in a moment of rapt attention, his eyes focused on the text before him. Learning was clearly the hallmark of traditional Jewish life. The walls were plain but the book case was handsome, filled with beautiful leather bound volumes.

helenw@bigpond.net.au

Talented Jewish artists emerged. Moritz Oppenheim (1800-82), Solomon Hart (1806–81), Jozef Israels (1824–1911), Alphonse Levy (1843-1918), Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-79), Solomon J Solomon (1860–1927), Samuel Hirszenberg (1865-1908), Boris Schatz (1867-1932) and Ephraim Lilien (1874–1925) were certainly creating worthy careers for themselves. Max Liebermann (1847-1935) was regarded as a pioneer of modern artistic development.

But in my opinion, the most important of all C19th Jewish artists was Hungarian-born Isidor Kaufmann (1853-1921). Young Kaufmann studied at the professional art academy of Budapest, and Vienna, for a total of 5 years. Then he married a synagogue cantor's daughter in 1882, and had 5 children. This was a painter who knew the outside art world but who was also very much a part of the large, traditional Jewish community in Vienna.

The question to ask is: could Kaufmann and these other young Jewish artists join the modern art world or would they be limited to depicting religious events, Biblical characters and rabbis’ portraits? Richard Cohen in “Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe” said that Kaufmann was less concerned than Moritz Oppenheim with encompassing the Jewish holidays, but more involved in uncovering the inner spirit of the Eastern European Jews in their daily life. I want to test Cohen’s view.

From the mid 1880s, Kaufmann began producing detailed genre paintings i.e subjects taken from everyday life. Luckily he was an excellent draughtsman and colourist. There paintings were very small in size and in subject matter, but then genre painting has nothing going for it except for honesty and domesticity. The paintings were set in cold, bare and totally un-idyllic contexts, but with lots of pleasure coming from friendship, family closeness or religious studies. And the details of a family home were painted with the same meticulousness that we might have expected from Vermeer, concentrating on the architectural detail of rooms and on the psychological authenticity of his models. There was not much politicising going on here.

But in my opinion, the most important of all C19th Jewish artists was Hungarian-born Isidor Kaufmann (1853-1921). Young Kaufmann studied at the professional art academy of Budapest, and Vienna, for a total of 5 years. Then he married a synagogue cantor's daughter in 1882, and had 5 children. This was a painter who knew the outside art world but who was also very much a part of the large, traditional Jewish community in Vienna.

The question to ask is: could Kaufmann and these other young Jewish artists join the modern art world or would they be limited to depicting religious events, Biblical characters and rabbis’ portraits? Richard Cohen in “Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe” said that Kaufmann was less concerned than Moritz Oppenheim with encompassing the Jewish holidays, but more involved in uncovering the inner spirit of the Eastern European Jews in their daily life. I want to test Cohen’s view.

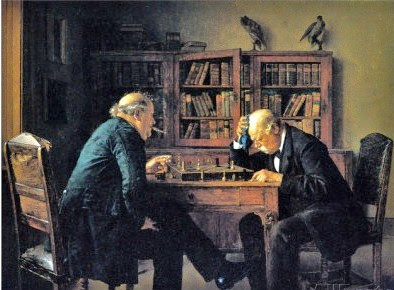

Kaufmann, The Chess Player

Sotheby's New York, 23rd June 1983,

26 x 21 cm

The Chess Player sat on a bare chair in a room of bare grey walls, his red nose, heavy coat and top hat suggesting the coldness of the space. But the cold didn’t matter. Intellectual pursuits were more important that fine furnishings: books remained open on a table, ready to be read again, once the chess strategies had been decided.

The Chess Players (c1886, not shown) there were two ordinary workers, friends sitting down to a quiet game at home. Their clothes were a very ordinary and they apparently couldn't afford to put even a rug on the floor, but the men were enjoying the contest and taking it very seriously. We assume that each chess decision was carefully considered, before each move was made.

Chess Problems dealt with a similar event, but this time the two men were considerably better dressed and the room was furnished with comfort and with style. While the composition of this painting was similar to the composition of The Chess Players, and the attention they paid to the game was similar, were the bare headed men were not Jewish? Presumbly it would not have mattered, in Vienna's contemporary world.

Consider the wide range of C19th Jewish artists who operated outside both ancient Rabbinic tradition and stark, secular modernism. In the suddenly mobile, changing world of the latter C19th, how could Jewish artists come to terms with their own identities and approach the task of representation? Appropriately The Emergence of Jewish Artists in C19th Europe, at New York's Jewish Museum 2001, presented 21 painters who offered radically different responses to this complex question. The book by the same name (Susan Tumarkian Goodman ed, Merrell Publishing NY, 2001) is excellent.

Richard McBee suggested Jewish artists like Kaufmann were able to address a broad public for the first time; they were interested in representing Jewish life and showing it to be on a par with Christian life. Their art documenting everyday life was shaped by the community and changed by modernity, so it had to do a balancing act between emancipation and assimilation. Kaufmann reminded the modern viewer that Jewish art acquired a changing and vital importance as an aspect of cultural identity.

The Chess Players (c1886, not shown) there were two ordinary workers, friends sitting down to a quiet game at home. Their clothes were a very ordinary and they apparently couldn't afford to put even a rug on the floor, but the men were enjoying the contest and taking it very seriously. We assume that each chess decision was carefully considered, before each move was made.

Kaufmann, Chess Problems

c1889, 31 x 40 cm

Chess Problems dealt with a similar event, but this time the two men were considerably better dressed and the room was furnished with comfort and with style. While the composition of this painting was similar to the composition of The Chess Players, and the attention they paid to the game was similar, were the bare headed men were not Jewish? Presumbly it would not have mattered, in Vienna's contemporary world.

Kaufmann, Two Pairs of Shoes

c1889, 38 x 31 cm

In Two Pairs of Shoes, an elderly Jewish man was shown assessing his stock from the table top where he sat. Perhaps business was going well enough; there seemed to have been a quiet smile on his face, and a satisfying cigarette in his hand. Clothes and shoes were heaped everywhere, in the suit case, on top of the table and over the screen. Note the detailed attention paid to the books, clock and vase in the back of the room.

Kaufmann, Commerical Instruction

1890-1, 40 x 31 cm

private collection

Commercial Instruction used a title similar to Business Secret but was more tender. Using virtually the same furniture and lights as The Rabbi's Visit, this painting told the story of a religious father and son spending time together. However instead of bonding over religious studies, this father was teaching his son about business. The lesson must have been appealing because the little boy was fascinated.

Kaufmann, Business Secret

c1894, 33 x 28 cm

In Isidor Kaufmann by G Tobias Natter (1995) I found eleven small, wonderful genre scenes painted in 1884-95. Two Pairs of Shoes, The Chess Players, No Fool Like An Old Fool, Chess Problems, Rabbi's Visit, Business Secret, Commercial Instruction, A Business Transaction etc were all painted in the corner of a lounge room, usually with one or two figures. In this short period, Kaufmann struck a gold mine, as it were. He created detailed, finished and painterly works, about small issues. Pleasure, religious or secular, was depicted.

Business Secret showed two poorly dressed men talking confidentially about secondhand items for sale. A third man poked his head through the window, possibly eavesdropping on the deal. By stressing the shabby hawkers with blatantly Jewish features, Natter suggested this painting verged on the cartoonish. But I think it was painted very much in the same tender vein as the others.

Business Secret showed two poorly dressed men talking confidentially about secondhand items for sale. A third man poked his head through the window, possibly eavesdropping on the deal. By stressing the shabby hawkers with blatantly Jewish features, Natter suggested this painting verged on the cartoonish. But I think it was painted very much in the same tender vein as the others.

Consider the wide range of C19th Jewish artists who operated outside both ancient Rabbinic tradition and stark, secular modernism. In the suddenly mobile, changing world of the latter C19th, how could Jewish artists come to terms with their own identities and approach the task of representation? Appropriately The Emergence of Jewish Artists in C19th Europe, at New York's Jewish Museum 2001, presented 21 painters who offered radically different responses to this complex question. The book by the same name (Susan Tumarkian Goodman ed, Merrell Publishing NY, 2001) is excellent.

Richard McBee suggested Jewish artists like Kaufmann were able to address a broad public for the first time; they were interested in representing Jewish life and showing it to be on a par with Christian life. Their art documenting everyday life was shaped by the community and changed by modernity, so it had to do a balancing act between emancipation and assimilation. Kaufmann reminded the modern viewer that Jewish art acquired a changing and vital importance as an aspect of cultural identity.

Kaufmann, Rabbi with a Young Student,

53 x 68 cm,

Sotherby's New York, 19th Dec 2012

53 x 68 cm,

Sotherby's New York, 19th Dec 2012

Then something changed for Kaufmann. Viennese genre scenes no longer satisfied the need to discover his vibrant Jewish roots. In the later 1890s, he chose to go in search of material in Jewish towns across the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Poland. He travelled every summer and returned to his Vienna studio to turn the sketches into completed paintings.

A work from this later era was Rabbi with A Young Student. Kaufmann reflected the pride he felt for the traditional religious life. The teacher displayed a sense of solemnity and perhaps wisdom. The young student was caught in a moment of rapt attention, his eyes focused on the text before him. Learning was clearly the hallmark of traditional Jewish life. The walls were plain but the book case was handsome, filled with beautiful leather bound volumes.

helenw@bigpond.net.au