The film A Quiet Passion depicts the poet Emily Dickinson entirely inside her home. Before seeing the film, I needed to understand Emily's inner life & family experience. Thank you Biography.

Let's start with Emily's father. Educated at Amherst and Yale, Edward Dickinson returned home, joined the family law practice and moved into the family house, The Homestead (1813). He was elected to Massachusetts State Legislature (1837-9) and the State Senate (1842-3). Between 1852-5 he served as a state representative in the Congress and treasurer of Amherst College. Edward’s wife was represented as the passive wife of a domineering husband.

There were three Dickinson children: Austin, middle child Emily and younger sister Lavinia. All three children attended the tiny primary school in Amherst and then moved on to Amherst Academy, the school out of which Amherst College had grown. Austin was later sent to Williston Seminary.

Emily was at Amherst Academy until 1847. Her time at the Academy provided her with her first Master, the principal Leonard Humphrey. Although Dickinson quite admired him while she was a student, her response to his unexpected death in 1850 identified her growing interest in passionate poetry. The other significant figure was Edward Hitchcock, president of Amherst College. a man devoted his life to maintaining the connection between the natural world and its divine Creator. He was a frequent lecturer at the Academy, and Emily often heard him speak.

**

Once I had read everything that was ever written about Emily Dickinson, it was time to see the film A Quiet Passion. Cynthia Nixon’s role as Emily Dickinson was very moving, an intelligent woman who displayed her bizarre mixture of humour, wit, free thought and a pained soul. Emily's important attachment to her close knit family was lovingly displayed in the film, even when the pain caused by her father and brother limited her life even more. Only the sister Vinnie and the female friends were constantly supportive, regardless of 1850s religious values in the USA.

In the film, the reverend led the family in prayer. Only Emily remained seated while the rest of the Dickinson family got down on their knees.

The photography was lush, detailed and sensitively handled. The clothes were beautifully recreated, as were the architecture and decorative arts in The Homestead. And best of all, Emily’s poetry was recited throughout the film which was excellent for those in the audience who did not study Dickinson at university. But except for one editor who said women could never write well, it was not clear at all why Emily’s special talent was only recognised and published four years after her death.

The film was 2 hours and 10 minutes long. I would have eliminated the last death scene which was irrelevant to the Dickinson story and would have reduced the film by 10-14 minutes.

Let's start with Emily's father. Educated at Amherst and Yale, Edward Dickinson returned home, joined the family law practice and moved into the family house, The Homestead (1813). He was elected to Massachusetts State Legislature (1837-9) and the State Senate (1842-3). Between 1852-5 he served as a state representative in the Congress and treasurer of Amherst College. Edward’s wife was represented as the passive wife of a domineering husband.

There were three Dickinson children: Austin, middle child Emily and younger sister Lavinia. All three children attended the tiny primary school in Amherst and then moved on to Amherst Academy, the school out of which Amherst College had grown. Austin was later sent to Williston Seminary.

Emily was at Amherst Academy until 1847. Her time at the Academy provided her with her first Master, the principal Leonard Humphrey. Although Dickinson quite admired him while she was a student, her response to his unexpected death in 1850 identified her growing interest in passionate poetry. The other significant figure was Edward Hitchcock, president of Amherst College. a man devoted his life to maintaining the connection between the natural world and its divine Creator. He was a frequent lecturer at the Academy, and Emily often heard him speak.

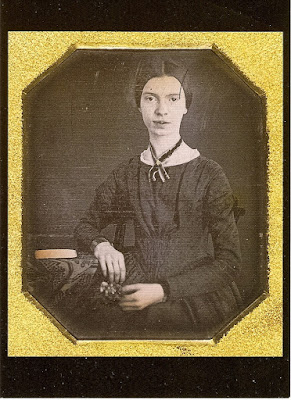

Emily Dickinson 1847.

Amherst College Collections.

At the Academy Emily developed a group of close friends. As was common for young, middle class women, the formal schooling they received in the academies provided them with some autonomy and intellectual rigour. Many of the women’s academies required full-day attendance, with the same curriculum as young men’s education.

In the 1847-8 academic year, Emily attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, a school noted for its religious stance. The school also prided itself on its connection with Amherst College, offering students college lectures in astronomy, botany, chemistry, geology, mathematics etc. Later the curriculum’s C19th emphasis on science reappeared often in Emily’s poems and letters.

At the Academy Emily developed a group of close friends. As was common for young, middle class women, the formal schooling they received in the academies provided them with some autonomy and intellectual rigour. Many of the women’s academies required full-day attendance, with the same curriculum as young men’s education.

In the 1847-8 academic year, Emily attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, a school noted for its religious stance. The school also prided itself on its connection with Amherst College, offering students college lectures in astronomy, botany, chemistry, geology, mathematics etc. Later the curriculum’s C19th emphasis on science reappeared often in Emily’s poems and letters.

So why was Emily’s stay at Mount Holyoke shortened from two years to one - reclusiveness? homesickness? lack of intimates? not fully part of school activities? father forbade it? lack of faith? No-one knew.

Just then Amherst was having a religious revival. The community loved the ministers’ strong preaching and the Dickinson household was affected eg Vinnie and Edward Dickinson soon counted themselves among the saved. Austin joined the church in 1856, his marriage year. Christ was calling everyone; only Emily was standing alone in rebellion.

Emily’s departure from Mount Holyoke marked the end of her formal schooling and prompted the dissatisfaction typical of educated young women in the mid C19th. Back at home, unmarried daughters were expected to resume their dutiful, selfless nature ☹

Since receiving and paying visits were essential to social standing, Vinnie and Emily Dickinson got busy. In a 1855 visit, the sisters stayed with an old Amherst friend in Philadelphia, and attended church with her. The minister was Rev Charles Wadsworth, famous for both his preaching and pastoral care! Shortly after a visit to Emily’s home in 1860, Rev Wadsworth left town, and this led to the heartsick flow of verse from Emily. The nature of her poetic love, to Wadsworth and others, still prompts scholars to ask: what did Dickinson’s passionate language signify?

Emily’s ambivalence toward marriage was telling. Married women, including her mother, had failing health and unmet demands that were parts of the husband-wife relationship. Writing to Susan Gilbert in the midst of Susan’s courtship with Austin Dickinson, Emily distinguished between the supposed joy of marriage and the parched life of the married woman. Emily clearly looked to her future sister-in-law as one of her most trusted readers.

With their father’s move to Washington, Austin gradually took over his father’s role. His marriage to Susan Gilbert in July 1856 brought a new sister into the family, one with whom Emily had much in common. Dad Edward eventually returned his family to the Homestead, Emily’s childhood home. Now she was writing hundreds of poems and letters in the rooms she had known for most of her life. Even better, Austin and Susan Dickinson settled in The Homestead, the new house next door to The Evergreens.

Emily never liked to visit others and didn’t invite people to visit her because the energy that visits required was mind-numbing. Was she a real recluse, or was she simply being practical? Instead letter-writing was visiting at its best!

The late 1850s saw Dickinson’s greatest poetic period. Those 1,100 poems already carried the familiar metric pattern of the hymn. Clearly her years were filled with both poems and letters. And reading. Emily read the contemporary authors on both sides of the Atlantic: Romantic poets, Charles Darwin, Brontë sisters, the Brownings, Thomas Carlyle, Matthew Arnold and George Eliot (UK) and Longfellow, Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Emerson (USA).

Just then Amherst was having a religious revival. The community loved the ministers’ strong preaching and the Dickinson household was affected eg Vinnie and Edward Dickinson soon counted themselves among the saved. Austin joined the church in 1856, his marriage year. Christ was calling everyone; only Emily was standing alone in rebellion.

Emily’s departure from Mount Holyoke marked the end of her formal schooling and prompted the dissatisfaction typical of educated young women in the mid C19th. Back at home, unmarried daughters were expected to resume their dutiful, selfless nature ☹

Since receiving and paying visits were essential to social standing, Vinnie and Emily Dickinson got busy. In a 1855 visit, the sisters stayed with an old Amherst friend in Philadelphia, and attended church with her. The minister was Rev Charles Wadsworth, famous for both his preaching and pastoral care! Shortly after a visit to Emily’s home in 1860, Rev Wadsworth left town, and this led to the heartsick flow of verse from Emily. The nature of her poetic love, to Wadsworth and others, still prompts scholars to ask: what did Dickinson’s passionate language signify?

Emily’s ambivalence toward marriage was telling. Married women, including her mother, had failing health and unmet demands that were parts of the husband-wife relationship. Writing to Susan Gilbert in the midst of Susan’s courtship with Austin Dickinson, Emily distinguished between the supposed joy of marriage and the parched life of the married woman. Emily clearly looked to her future sister-in-law as one of her most trusted readers.

Emily never liked to visit others and didn’t invite people to visit her because the energy that visits required was mind-numbing. Was she a real recluse, or was she simply being practical? Instead letter-writing was visiting at its best!

The late 1850s saw Dickinson’s greatest poetic period. Those 1,100 poems already carried the familiar metric pattern of the hymn. Clearly her years were filled with both poems and letters. And reading. Emily read the contemporary authors on both sides of the Atlantic: Romantic poets, Charles Darwin, Brontë sisters, the Brownings, Thomas Carlyle, Matthew Arnold and George Eliot (UK) and Longfellow, Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Emerson (USA).

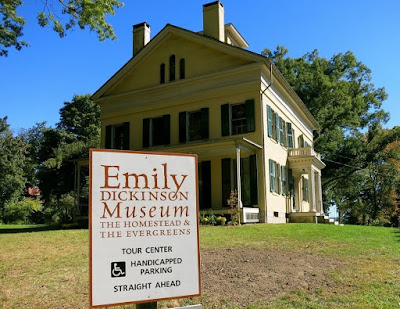

The Homestead was the birthplace and home of the poet Emily Dickinson.

The Evergreens, next door, was home to her brother Austin and sister in law Susan.

The Evergreens, next door, was home to her brother Austin and sister in law Susan.

In 1862 she wrote to literary man Thomas Higginson in response to his Atlantic Monthly, and sent him four poems. Higginson was curious, but he didn’t yet see a published poet emerging from her “poorly structured” poetry. Instead he counselled her to work harder on her poetry before she tried publishing it. Nonetheless Emily’s unpublished poems circulated widely among her family and friends, since this audience was part of women’s literary culture in the mid C19th.

Emily Dickinson died in Amherst in 1886, not publicly recognised during her lifetime. Only when her family discovered volumes of poems and posthumously published them in 1890 did she find acclaim.

Emily Dickinson died in Amherst in 1886, not publicly recognised during her lifetime. Only when her family discovered volumes of poems and posthumously published them in 1890 did she find acclaim.

**

Once I had read everything that was ever written about Emily Dickinson, it was time to see the film A Quiet Passion. Cynthia Nixon’s role as Emily Dickinson was very moving, an intelligent woman who displayed her bizarre mixture of humour, wit, free thought and a pained soul. Emily's important attachment to her close knit family was lovingly displayed in the film, even when the pain caused by her father and brother limited her life even more. Only the sister Vinnie and the female friends were constantly supportive, regardless of 1850s religious values in the USA.

In the film, the reverend led the family in prayer. Only Emily remained seated while the rest of the Dickinson family got down on their knees.

The photography was lush, detailed and sensitively handled. The clothes were beautifully recreated, as were the architecture and decorative arts in The Homestead. And best of all, Emily’s poetry was recited throughout the film which was excellent for those in the audience who did not study Dickinson at university. But except for one editor who said women could never write well, it was not clear at all why Emily’s special talent was only recognised and published four years after her death.

The film was 2 hours and 10 minutes long. I would have eliminated the last death scene which was irrelevant to the Dickinson story and would have reduced the film by 10-14 minutes.