The early-middle 19th century was full of war eg1 the Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815) devastated Europe. Eg2 The Anglo-American War of 1812 involved a war against British shipping and repeated American invasions of Canada. Eg3 The Crimean War (1853–1856) led to 300,000 dead or imprisoned from the British-French-Turkish side and 220,000 dead or imprisoned Russians.

These wars devised cartel ships for the exchange of prisoners of war, even while the armies were still fighting. Cartels were ships employed on humanitarian trips, to safely carry prisoners for repatriation to their homes. While serving as a legitimate cartel, a ship could not be captured by enemy action.

During the later C19th, nations wanted to improve the treatment of prisoners of war in enemy countries, AND their safe return home after the war. Multi-national conferences were held, most notably the Brussels Conference of 1874. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, ongoing negotiations led to new conventions being recognised. In international law, prisoners of war were to be treated humanely.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, formally founded in 1863 in Geneva, had a special task within international humanitarian law. For this post, the ICRC's most important task was to establish the International Prisoners of War Agency in Geneva, in August 1914. Its role was to restore contact between people separated by war – prisoners of war, civilian internees and civilians in occupied territories. During WW1, the Agency kept information on almost two and a half million POWs. It also ensured prisoners of war had the right to send and receive family letters.

Tsar Nicholas II strongly encouraged international conferences that fixed the terms of the laws and customs of war, firstly at The Hague in 1899 (and later in 1907). The final principles were published by the Hague Convention of 1899 in Articles 3-20, including:

*In case of capture by the enemy, combatants and others have a right to be treated as prisoners of war. They must be humanely treated.

*All their personal belongings, except arms, horses and military papers remain their property.

*The State may utilise prisoner of war labour according to their rank and aptitude. Their tasks shall not be excessive, and shall have nothing to do with the military operations.

*The wages of the prisoners shall go towards improving their position, and the balance shall be paid them at the time of their release, after deducting the cost of their maintenance.

*Failing a special agreement between the belligerents, prisoners of war shall be treated on the same footing as local troops, as regards food, housing and clothing.

*Relief Societies for prisoners of war shall receive, from the belligerents for themselves and their duly accredited agents, every facility for the effective accomplishment of their humane task.

Britain At War 1915 (p22) noted that by the early weeks of 1915, the British and German governments had to urgently consider the internment and/or exchange of wounded POWs. The Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs told the House of Commons in March 1915 that both the British and the German Governments “had agreed to the principle of an exchange of POWs permanently incapacitated for further military service”. All negotiations for the exchange of prisoners were to be conducted through the Foreign Office, with the concurrence of the War Office.

These wars devised cartel ships for the exchange of prisoners of war, even while the armies were still fighting. Cartels were ships employed on humanitarian trips, to safely carry prisoners for repatriation to their homes. While serving as a legitimate cartel, a ship could not be captured by enemy action.

During the later C19th, nations wanted to improve the treatment of prisoners of war in enemy countries, AND their safe return home after the war. Multi-national conferences were held, most notably the Brussels Conference of 1874. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, ongoing negotiations led to new conventions being recognised. In international law, prisoners of war were to be treated humanely.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, formally founded in 1863 in Geneva, had a special task within international humanitarian law. For this post, the ICRC's most important task was to establish the International Prisoners of War Agency in Geneva, in August 1914. Its role was to restore contact between people separated by war – prisoners of war, civilian internees and civilians in occupied territories. During WW1, the Agency kept information on almost two and a half million POWs. It also ensured prisoners of war had the right to send and receive family letters.

Tsar Nicholas II strongly encouraged international conferences that fixed the terms of the laws and customs of war, firstly at The Hague in 1899 (and later in 1907). The final principles were published by the Hague Convention of 1899 in Articles 3-20, including:

*In case of capture by the enemy, combatants and others have a right to be treated as prisoners of war. They must be humanely treated.

*All their personal belongings, except arms, horses and military papers remain their property.

*The State may utilise prisoner of war labour according to their rank and aptitude. Their tasks shall not be excessive, and shall have nothing to do with the military operations.

*The wages of the prisoners shall go towards improving their position, and the balance shall be paid them at the time of their release, after deducting the cost of their maintenance.

*Failing a special agreement between the belligerents, prisoners of war shall be treated on the same footing as local troops, as regards food, housing and clothing.

*Relief Societies for prisoners of war shall receive, from the belligerents for themselves and their duly accredited agents, every facility for the effective accomplishment of their humane task.

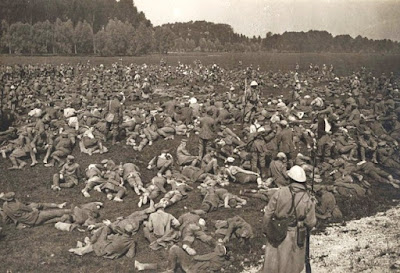

German prisoners lying and waiting in a field at Longueau

on the Western Front, August 1916

Photo credit: The Telegraph 12th Nov 2015

But the only thing this 1899 Hague Convention said specifically about the exchange of POWs was as follows: “After the conclusion of peace, the repatriation of prisoners of war shall take place as speedily as possible”.

The Hague Conventions came into force in the German Empire and France in January 1910, but then World War One changed everything. Already by September 1914, 125,000 French soldiers and 94,000 Russian POWs were held captive in German camps. And not just in Germany itself. Very soon POW camps were opened for business in Germany’s occupied territories, especially in northern and eastern France. I wonder how many German POWs were captured and held in Allied prison camps at the same time.

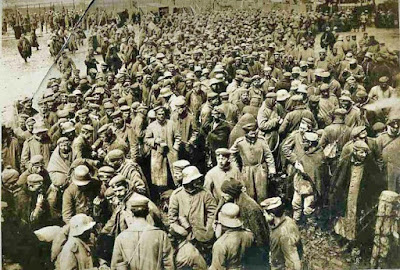

German prisoners being readied for transport home,

20th November 1918

Photo credit: Central News Photo Service

But the only thing this 1899 Hague Convention said specifically about the exchange of POWs was as follows: “After the conclusion of peace, the repatriation of prisoners of war shall take place as speedily as possible”.

The Hague Conventions came into force in the German Empire and France in January 1910, but then World War One changed everything. Already by September 1914, 125,000 French soldiers and 94,000 Russian POWs were held captive in German camps. And not just in Germany itself. Very soon POW camps were opened for business in Germany’s occupied territories, especially in northern and eastern France. I wonder how many German POWs were captured and held in Allied prison camps at the same time.

German prisoners being readied for transport home,

20th November 1918

Photo credit: Central News Photo Service

Britain At War 1915 (p22) noted that by the early weeks of 1915, the British and German governments had to urgently consider the internment and/or exchange of wounded POWs. The Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs told the House of Commons in March 1915 that both the British and the German Governments “had agreed to the principle of an exchange of POWs permanently incapacitated for further military service”. All negotiations for the exchange of prisoners were to be conducted through the Foreign Office, with the concurrence of the War Office.

One exchange under this agreement had already been effected, on 15th February 1915. It involved a number of disabled, seriously ill or badly wounded British and German POWs. Those participating Allied prisoners who were held in camps in central and southern Germany were transferred via neutral Switzerland, whilst those incarcerated in the east and north went via neutral Netherlands. The intention was that these prisoners would be held in camps in those neutral countries and nursed back to health before completing their repatriation.

The other neutral nation to get involved in 1915 was the USA. The American Ambassador to Berlin, James Gerard, acted as a mediator between the two warring nations. Gerard was delighted to see that the wounded and sick officers and men were sent to Switzerland, still as prisoners of war. From there, they were subject to return to Germany or Great Britain respectively.

There were over 8 million soldiers taken prisoner during WWI. Yet I can find no more formal agreements for the repatriation of POWs until the Treaty of Versailles (articles 214-226), signed in 1919.

The other neutral nation to get involved in 1915 was the USA. The American Ambassador to Berlin, James Gerard, acted as a mediator between the two warring nations. Gerard was delighted to see that the wounded and sick officers and men were sent to Switzerland, still as prisoners of war. From there, they were subject to return to Germany or Great Britain respectively.

There were over 8 million soldiers taken prisoner during WWI. Yet I can find no more formal agreements for the repatriation of POWs until the Treaty of Versailles (articles 214-226), signed in 1919.