Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979) was an American collector, patron, dealer and later the founder of her own museum. She successfully stayed at the centre of the modern art world in New York, Paris, London and Venice for 50 years. Yet Francine Prose, in her 2015 book Peggy Guggenheim, The Shock of the Modern, wrote that Peggy was equally famous for her unconventional personal life.

Now I am asking the students to examine Peggy Guggenheim more personally, examining her patronage and avant-garde art exhibitions of course but also looking at her families of origin, her own marriages, her revolutionary sex life, the celebrity friendships, finances, mental health issues, gender issues and anti-Semitism. Peggy may have been a strong, uncompromising woman who exercised influence in a male-dominated world but there were surprising (to me) prices that had to be paid.

It all started in the later C19th; the American Guggenheim family bought smelters and refineries, formed an exploration company to purchase metals and diamond mines in the USA, Africa and Latin America and became very wealthy. Benjamin Guggenheim married Florette Seligman in 1894; their first daughter Benita arrived in 1895, Marguerite/Peggy in 1898 and Hazel in 1903.

Now here is something I had never heard before. Peggy’s Seligman grandmother, mother, aunts and uncles were phobic about germs. One uncle killed himself in his 50s (suicide?) and two cousins were definitely suicides. At twenty, Peggy suffered a nervous collapse because of her compulsive behaviours. And when in 1928 Hazel’s sons died in a fall from a high building in Manhattan, questions about the family’s mental health were raised again.

Prose was certain that by her family’s own standards, Peggy wasn’t very rich. Her beloved father Benjamin had decamped to France and she missed him dreadfully. Then he went down with the Titanic in 1912. Benjamin’s death made it clear that he had lost millions on his Parisian business, a company that wanted to install elevators in the Eiffel Tower. So the Guggenheim uncles convened to decide how to maintain the widow Florette and the young three girls decently. Florette moved her daughters to more modest quarters.

By the time Peggy came of age in 1919 she began to think of herself as The Problematic Guggenheim. Having received her first big inheritance from her late father, Peggy immediately fled the haute bourgeoisie of her privileged childhood in the USA for the European bohemian world. Later Peggy received another large sum of money when her mother died in 1937, but she remained utterly insecure about money for decades.

Peggy first mentioned her inferiority complex in connection with the world of social and sexual opportunity from which she felt she was excluded because she was ugly. If she could not be beautiful, she compensated by being seductive and liberated. In any case, plastic surgery in 1920 failed her.

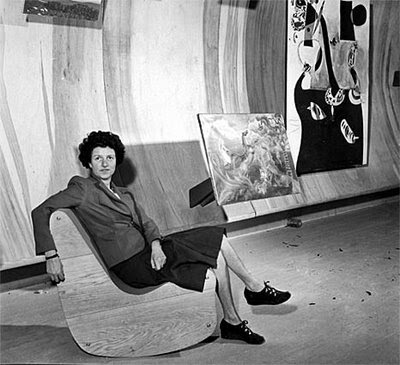

Because her sisters were great beauties and because Peggy felt she was ugly, her frenetic sex life was attributed to insecurity about her nose. (Her photos suggest she was a perfectly fine looking young woman). And there were other issues. Firstly Peggy claimed never to have recovered from the loss of her father. For the rest of her life, she wrote, she would look for a man to replace him. Secondly Peggy also believed her intellectual inadequacy was corrosive, confirmed and exaggerated by husband Laurence Vail.

There was no stronger advocate for groundbreaking arts. As early as 1925 Peggy financed the opening of a shop in Paris to showcase the lampshades designed by her friend the poet Mina Loy; the shop also hosted an exhibition of Laurence’s paintings. Though the boutique failed, it represented Peggy’s first attempt to exhibit and sell art.

Peggy continued to publicise and tirelessly champion a list of painters and sculptors whose names soon towered in the history of modernism. After Paris, she moved to London and in 1938 opened the critically acclaimed gallery Guggenheim Jeune.

Peggy’s eye for art seemed very forward-looking, particularly when compared to the established museums. When the removal of her artwork from her Paris home became urgent with the imminent German invasion of France, the Louvre refused to hide her holdings of works by Leger, Kandinsky, Klee, Picabia, Dali, Miro, Brancusi and Duchamp. These artists’ painting were judged to be too modern to “hide amongst the Louvre’s own collection”. And the director of the Tate ruled that Peggy’s Arps and Brancusis did not qualify as sculpture for customs purposes. Duchamp solved one problem - he suggested packing his boxes among Peggy's personal possessions that were being shipped to New York.

Peggy became both the financial backer on whom the others depended, [as well as the target for endless complaints of her miserliness]. Among the recipients of her bounty were not only artists, but also striking British miners. A young Harvard-educated American journalist, Varian Fry, had witnessed Nazi atrocities and joined the Emergency Rescue Committee in Marseille. Peggy’s greatest life-saving gift was her huge donation to Varian Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee in 1940. The committee helped thousands escape Vichy France, especially artists and writers.

During the German occupation, Peggy donated enough money to get André Breton and his family out of France, and she married and supported Max Ernst long after they arrived in the USA. These were gifts, not loans. An even greater proportion of her inheritance was spent supporting painters and sculptors by buying their work.

Prose reported how Peggy boasted of having had 400+ lovers and two husbands. Think of Samuel Beckett, Giorgio Joyce, Yves Tanguy, Constantin Brancusi and Marcel Duchamp. Her first marriage, to the bohemian artist and writer Laurence Vail, produced two children and a history of spousal abuse that set the nasty pattern for the future; her second, to Max Ernst, was less obviously brutal but still demeaning. And there were episodes of violence with her lovers John Holms and Douglas Garman. How could an otherwise strong woman tolerate spousal abuse??

Now I am asking the students to examine Peggy Guggenheim more personally, examining her patronage and avant-garde art exhibitions of course but also looking at her families of origin, her own marriages, her revolutionary sex life, the celebrity friendships, finances, mental health issues, gender issues and anti-Semitism. Peggy may have been a strong, uncompromising woman who exercised influence in a male-dominated world but there were surprising (to me) prices that had to be paid.

It all started in the later C19th; the American Guggenheim family bought smelters and refineries, formed an exploration company to purchase metals and diamond mines in the USA, Africa and Latin America and became very wealthy. Benjamin Guggenheim married Florette Seligman in 1894; their first daughter Benita arrived in 1895, Marguerite/Peggy in 1898 and Hazel in 1903.

Now here is something I had never heard before. Peggy’s Seligman grandmother, mother, aunts and uncles were phobic about germs. One uncle killed himself in his 50s (suicide?) and two cousins were definitely suicides. At twenty, Peggy suffered a nervous collapse because of her compulsive behaviours. And when in 1928 Hazel’s sons died in a fall from a high building in Manhattan, questions about the family’s mental health were raised again.

Prose was certain that by her family’s own standards, Peggy wasn’t very rich. Her beloved father Benjamin had decamped to France and she missed him dreadfully. Then he went down with the Titanic in 1912. Benjamin’s death made it clear that he had lost millions on his Parisian business, a company that wanted to install elevators in the Eiffel Tower. So the Guggenheim uncles convened to decide how to maintain the widow Florette and the young three girls decently. Florette moved her daughters to more modest quarters.

By the time Peggy came of age in 1919 she began to think of herself as The Problematic Guggenheim. Having received her first big inheritance from her late father, Peggy immediately fled the haute bourgeoisie of her privileged childhood in the USA for the European bohemian world. Later Peggy received another large sum of money when her mother died in 1937, but she remained utterly insecure about money for decades.

Peggy Guggenheim opened Art of This Century Gallery

in New York in 1942

Because her sisters were great beauties and because Peggy felt she was ugly, her frenetic sex life was attributed to insecurity about her nose. (Her photos suggest she was a perfectly fine looking young woman). And there were other issues. Firstly Peggy claimed never to have recovered from the loss of her father. For the rest of her life, she wrote, she would look for a man to replace him. Secondly Peggy also believed her intellectual inadequacy was corrosive, confirmed and exaggerated by husband Laurence Vail.

There was no stronger advocate for groundbreaking arts. As early as 1925 Peggy financed the opening of a shop in Paris to showcase the lampshades designed by her friend the poet Mina Loy; the shop also hosted an exhibition of Laurence’s paintings. Though the boutique failed, it represented Peggy’s first attempt to exhibit and sell art.

Peggy continued to publicise and tirelessly champion a list of painters and sculptors whose names soon towered in the history of modernism. After Paris, she moved to London and in 1938 opened the critically acclaimed gallery Guggenheim Jeune.

Peggy’s eye for art seemed very forward-looking, particularly when compared to the established museums. When the removal of her artwork from her Paris home became urgent with the imminent German invasion of France, the Louvre refused to hide her holdings of works by Leger, Kandinsky, Klee, Picabia, Dali, Miro, Brancusi and Duchamp. These artists’ painting were judged to be too modern to “hide amongst the Louvre’s own collection”. And the director of the Tate ruled that Peggy’s Arps and Brancusis did not qualify as sculpture for customs purposes. Duchamp solved one problem - he suggested packing his boxes among Peggy's personal possessions that were being shipped to New York.

Peggy became both the financial backer on whom the others depended, [as well as the target for endless complaints of her miserliness]. Among the recipients of her bounty were not only artists, but also striking British miners. A young Harvard-educated American journalist, Varian Fry, had witnessed Nazi atrocities and joined the Emergency Rescue Committee in Marseille. Peggy’s greatest life-saving gift was her huge donation to Varian Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee in 1940. The committee helped thousands escape Vichy France, especially artists and writers.

During the German occupation, Peggy donated enough money to get André Breton and his family out of France, and she married and supported Max Ernst long after they arrived in the USA. These were gifts, not loans. An even greater proportion of her inheritance was spent supporting painters and sculptors by buying their work.

Prose reported how Peggy boasted of having had 400+ lovers and two husbands. Think of Samuel Beckett, Giorgio Joyce, Yves Tanguy, Constantin Brancusi and Marcel Duchamp. Her first marriage, to the bohemian artist and writer Laurence Vail, produced two children and a history of spousal abuse that set the nasty pattern for the future; her second, to Max Ernst, was less obviously brutal but still demeaning. And there were episodes of violence with her lovers John Holms and Douglas Garman. How could an otherwise strong woman tolerate spousal abuse??

Francine Prose's book,

Peggy Guggenheim: the Shock of the Modern

Yale UP, 2015

During the war Peggy travelled back to New York where she opened Art of This Century, an experimental combination of museum and gallery, in Oct 1942. Peggy launched Jackson Pollock, her greatest discovery, with an exhibit in 1943. Her contract with Pollock guaranteed an income in advance of sales, allowing the artist to devote himself to art. Within a few years Pollock’s prices began to take off.

In 1947, Peggy closed Art of This Century and moved to Venice, where she was invited to install her collection at the 1948 Biennale. Abstract Expressionists had arrived! That year she acquired a Venetian C18th palazzo that served for the rest of her life as both residence and museum. The Great and the Good, as well as the general public, were admitted three days a week.

In 1947, Peggy closed Art of This Century and moved to Venice, where she was invited to install her collection at the 1948 Biennale. Abstract Expressionists had arrived! That year she acquired a Venetian C18th palazzo that served for the rest of her life as both residence and museum. The Great and the Good, as well as the general public, were admitted three days a week.