My father graduated from university in Dec 1943 and became a Lieutenant and an engineer in the Australian Army in 1944 and 1945. When he passed away this week, I wanted to honour him with material that he gave me decades ago...on The Australian Women's Land Army. They were women doing a huge job, women he had been proud to work with.

My late father Les

Our Land At War: A Portrait of Rural Britain 1939-45 was written by Duff Hart-Davis (published by William Collins in 2015). Unlike histories that concentrated on British service men and women on the Continent, this book discussed how European warfare began to affect the civilian population back in rural Britain. Apart from the risk of bombs that the entire nation faced, rural Britain also had to deal with finding local young men to join up; paying higher taxes; providing homes for motherless children evacuated from the cities, the arbitrary conversion of pasture land into training camps, firing ranges and airfields; and the arrival of many of soldiers and foresters from across the British Empire. Prisoner-of-war camps meant that captured enemy soldiers lived near rural towns and villages; and farmers faced new restrictions on what they could grow on their own property.

At home, women had to deal with the inevitable costs of war by themselves: raising children alone, managing family finances on one or no salary, inadequate food and heating, and the grief of having fathers and brothers killed, wounded or captured.

In the early 1950s I had heard so much about the wonderful Women’s Land Army in Australia, so now I have become interested in the Women's Land Army in Britain as well. As British men were conscripted, women were needed to work the land and there was no doubt that the culture shock was felt on both sides of the gender divide. The young women challenged cultural assumptions regarding gender and femininity; both farmers and male rural workers had to change their thinking about women workers very quickly.

It was not a doddle. As the Land Girls lived either on the farms where they worked, or nearby in hostels, the young women had to deal with missing their family and friends. Then these young city women were confronted with the daily ordeals of really heavy farm work. Parts of the Land Girl uniform were hated by the women who felt lumpen in them. And the pay was dismal. Land Girls earned only £1.85 for a 50 hour working week, although in 1944, their wages were increased to £2.85. Worse still Land Girls laboured long and hard, often without enough daily protein.

In 1997, many Land Army women became eligible for the Civilian Service Medal. But it took until the 70th anniversary of the organisation’s birth before the Australian Government recognised and thanked the now-elderly women for their heroic efforts. A reception was held in Parliament House in August 2012 where attendees were presented with a certificate, a brooch and a history publication of the AWLA. A bit late, I would have thought - how many women, old enough to work in 1942, survived till 2012?

My late father Les

Our Land At War: A Portrait of Rural Britain 1939-45 was written by Duff Hart-Davis (published by William Collins in 2015). Unlike histories that concentrated on British service men and women on the Continent, this book discussed how European warfare began to affect the civilian population back in rural Britain. Apart from the risk of bombs that the entire nation faced, rural Britain also had to deal with finding local young men to join up; paying higher taxes; providing homes for motherless children evacuated from the cities, the arbitrary conversion of pasture land into training camps, firing ranges and airfields; and the arrival of many of soldiers and foresters from across the British Empire. Prisoner-of-war camps meant that captured enemy soldiers lived near rural towns and villages; and farmers faced new restrictions on what they could grow on their own property.

At home, women had to deal with the inevitable costs of war by themselves: raising children alone, managing family finances on one or no salary, inadequate food and heating, and the grief of having fathers and brothers killed, wounded or captured.

In the early 1950s I had heard so much about the wonderful Women’s Land Army in Australia, so now I have become interested in the Women's Land Army in Britain as well. As British men were conscripted, women were needed to work the land and there was no doubt that the culture shock was felt on both sides of the gender divide. The young women challenged cultural assumptions regarding gender and femininity; both farmers and male rural workers had to change their thinking about women workers very quickly.

It was not a doddle. As the Land Girls lived either on the farms where they worked, or nearby in hostels, the young women had to deal with missing their family and friends. Then these young city women were confronted with the daily ordeals of really heavy farm work. Parts of the Land Girl uniform were hated by the women who felt lumpen in them. And the pay was dismal. Land Girls earned only £1.85 for a 50 hour working week, although in 1944, their wages were increased to £2.85. Worse still Land Girls laboured long and hard, often without enough daily protein.

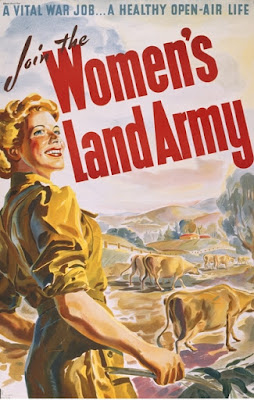

The British poster depicted a smiling, healthy young woman in a WLA uniform. She was looking over a dairy farm where she worked.

Nonetheless women joined up in great numbers, and by 1944 there were 80,000 women working on the land in Britain. The majority of these women thoroughly enjoyed the responsibility and the independence, and remained friends with other Land Girls long after the war ended.

**

Back at home, the Australian Women's Land Army (AWLA) was created in July 1942 in Australia to combat the inevitable farm-labour shortages that war brought. Based on Britain Women's Land Army, the AWLA’s task was to train and organise female workers to be employed by farmers whose male workforce had already left the countryside.

In January 1942 a Federal Manpower Directorate was established and took over responsibility for the list of reserved occupations. The Director-General of Manpower could exempt any person from service in the armed forces; declare which industries were protected and could require a permit for any change of employment. So it made sense that when state and private women’s land organisations began to form, it would be under of the control of the Director General of Manpower.

The minimum age for recruits was 18. The AWLA had two types of membership: a] Full-time members were enrolled for continuous service for 12 months or more. They received a dress uniform, working clothes and equipment. And b] Auxiliary members were available for periods of not less than four weeks at nominated times of the year, for seasonal rural operations. They received working clothes, and essential equipment on loan. The AWLA reached its peak enrolment in December 1943, with 2,400 permanent members and 1,000 auxiliary members.

Often unskilled in rural work, city women were given farming training and preparation for hard work. The Land Army women worked a 48 hour week, earning much less than their male counterparts for the same labour. Actively recruited into tough men’s jobs, these young women drove tractors, grew vegetables and fruits, raised pigs and poultry, cut timber and looked after sheep and wool.

Patsy Adam-Smith expressed it well: early in the war, Australian women had beaten a path to the doors of the authorities, begging to be allowed to assist, to help win the war, to give of their talents. After the war, the women felt proud of themselves, had made an important contribution to the war effort and had learned new employment skills. So the transition back to normal, when women were expected to give up their jobs for men who returned home from overseas conflicts, must have been horrible.

Join Us in a Victory Job 1943.

**

Back at home, the Australian Women's Land Army (AWLA) was created in July 1942 in Australia to combat the inevitable farm-labour shortages that war brought. Based on Britain Women's Land Army, the AWLA’s task was to train and organise female workers to be employed by farmers whose male workforce had already left the countryside.

In January 1942 a Federal Manpower Directorate was established and took over responsibility for the list of reserved occupations. The Director-General of Manpower could exempt any person from service in the armed forces; declare which industries were protected and could require a permit for any change of employment. So it made sense that when state and private women’s land organisations began to form, it would be under of the control of the Director General of Manpower.

The minimum age for recruits was 18. The AWLA had two types of membership: a] Full-time members were enrolled for continuous service for 12 months or more. They received a dress uniform, working clothes and equipment. And b] Auxiliary members were available for periods of not less than four weeks at nominated times of the year, for seasonal rural operations. They received working clothes, and essential equipment on loan. The AWLA reached its peak enrolment in December 1943, with 2,400 permanent members and 1,000 auxiliary members.

Often unskilled in rural work, city women were given farming training and preparation for hard work. The Land Army women worked a 48 hour week, earning much less than their male counterparts for the same labour. Actively recruited into tough men’s jobs, these young women drove tractors, grew vegetables and fruits, raised pigs and poultry, cut timber and looked after sheep and wool.

Patsy Adam-Smith expressed it well: early in the war, Australian women had beaten a path to the doors of the authorities, begging to be allowed to assist, to help win the war, to give of their talents. After the war, the women felt proud of themselves, had made an important contribution to the war effort and had learned new employment skills. So the transition back to normal, when women were expected to give up their jobs for men who returned home from overseas conflicts, must have been horrible.

Join Us in a Victory Job 1943.

This Australian recruiting poster was created in the Department of National Service. Services included the Australian Women’s Land Army, Australian Army Medical Women's Service and other military services

The AWLA disbanded on 31st Dec 1945 because theirs were jobs for the war, not for life. Even after the war, little credit was paid to the essential service the women provided. AWLA was not considered a military service so the women never received the benefits, eg pensions and special housing loans, that were available to those women who joined WRANS etc.

In 1997, many Land Army women became eligible for the Civilian Service Medal. But it took until the 70th anniversary of the organisation’s birth before the Australian Government recognised and thanked the now-elderly women for their heroic efforts. A reception was held in Parliament House in August 2012 where attendees were presented with a certificate, a brooch and a history publication of the AWLA. A bit late, I would have thought - how many women, old enough to work in 1942, survived till 2012?