The Impressionist artists were irreversibly split over the Dreyfus Affair from 1894 on, the crisis that split all of France. Monet, Pissarro, Signac and Vallotton, as well as art critics Mirbeau and Feneon supported Captain Dreyfus. Those on the opposite side included Degas, Cezanne, Renoir and Armand Guillaumin. When asked to sign the pro-Dreyfus Manifesto of the Intellectuals, Monet, Signac and Pissarro signed; Renoir refused.

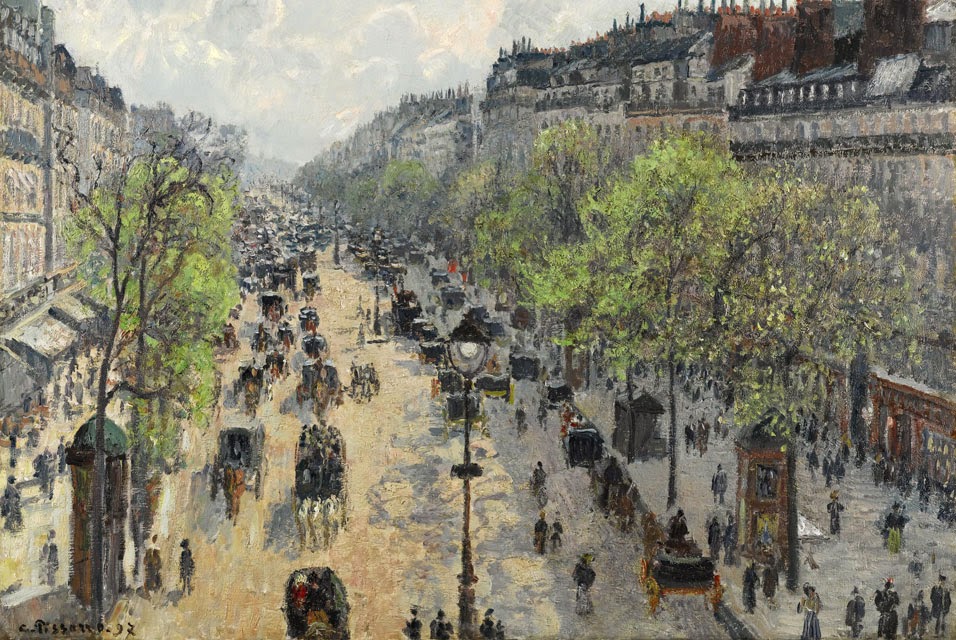

Manet was dead and Degas, Cezanne and Renoir never spoke to their old friends again. As a result, Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) was a rather distressed and lonely old man by the time he painted Le Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps in 1897. So he stayed inside his upper floor flat and painted the busy spring scene through the window. Thus the elevated perspective.

He died a few years later.

This version of Boulevard Montmartre moved through the hands of two of my favourite art dealers: Galerie Durand-Ruel in Paris who acquired it from the artist in June 1898; and Paul Cassirer in Berlin who acquired it from Durand-Ruel in October 1902. Of all the occasions on which this painting was exhibited to the public, the most important were at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in Paris in 1898 (Recent Works by Pissarro); and at Wildenstein in New York in 1970 (One Hundred Years of Impressionism’: A Tribute to Durand-Ruel).

Camille Pissarro, 1897

Boulevard Montmartre, spring morning

65 by 81cm.

By 1923 the painting was in the impressive collection of the German industrialist Max Silberberg from Breslau. He assembled an art collection that included fine French Impressionist works by Manet, Monet, Renoir and Sisley, as well as masterpieces of Realism and Post-Impressionism by Cézanne and van Gogh. At the time he was ranked as an internationally famous collector alongside Andrew Mellon, Jakob Goldschmidt and Mortimer Schiff. So naturally his treasures were requested for exhibitions around the world. As late as 1933, Max Silberberg's paintings were generously loaned for shows in Vienna and New York.

Silberberg, who was forced by the Nazis to dispose of the work in a Berlin sale in 1935, was exterminated in Auschwitz with his wife. In 1999, Max’s daughter in law Gerta Silberberg became the first British relative of a Holocaust victim to recover a work of art under the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-looted art. In 2000 the small painting was placed on loan with the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

artdaily noted that Camille Pissarro’s series paintings of Paris were among the supreme achievements of Impressionism, taking their place alongside Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral. Pissarro worked methodically for over two months on his Boulevard Montmartre series and held this particular painting in especially high esteem, writing to his dealer Durand-Ruel, ‘I have just received an invitation from the Carnegie Institute for this year’s exhibition: I’ve decided to send them the painting Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps… So please do not sell it’.

Pissarro’s paintings of Paris executed in the last years of the 1890s were hugely significant achievements that brilliantly evoke the excitement and spectacle of the city at the fin-de-siècle. For an artist who throughout his earlier career was primarily celebrated as a painter of rural life rather than the urban environment, the Boulevard Montmartre series was among a small group that confirmed his position as the preeminent painter of the city. Pissarro was able to exploit the artistic possibilities presented by the new urban landscape of Paris that Baron Haussmann’s renovations to the city had created.

The art market agreed. In February 2014 the Pissarro painting was auctioned at Sotheby's in London, and sold for £19,682,500, double its pre-sale estimate and five times the previous record for this particular Impressionist.

Although this post is just about the Pissarro painting of Montmartre, I did wonder what happened to the other 143 works of art from the Silberberg collection that were sold by the Nazis in four separate auctions between 1933 and 1938. The Foundation for Prussian Cultural Heritage, the organisation responsible for German museums, approved the return of a Vincent van Gogh and a Hans von Marees when its president asked for special authorisation to restore property to the children of people who died in the Holocaust. In 1999 the Foundation was successful, avoiding protracted and painful court proceedings, at least for two of the 143 art objects. Van Gogh’s Olive groces with Les Alpilles in the background was restituted to Gerta Silberberg from the National Gallery of Berlin in 1999.

Was owned by Max Silberberg. Where is it now?

Manet was dead and Degas, Cezanne and Renoir never spoke to their old friends again. As a result, Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) was a rather distressed and lonely old man by the time he painted Le Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps in 1897. So he stayed inside his upper floor flat and painted the busy spring scene through the window. Thus the elevated perspective.

He died a few years later.

This version of Boulevard Montmartre moved through the hands of two of my favourite art dealers: Galerie Durand-Ruel in Paris who acquired it from the artist in June 1898; and Paul Cassirer in Berlin who acquired it from Durand-Ruel in October 1902. Of all the occasions on which this painting was exhibited to the public, the most important were at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in Paris in 1898 (Recent Works by Pissarro); and at Wildenstein in New York in 1970 (One Hundred Years of Impressionism’: A Tribute to Durand-Ruel).

Camille Pissarro, 1897

Boulevard Montmartre, spring morning

65 by 81cm.

By 1923 the painting was in the impressive collection of the German industrialist Max Silberberg from Breslau. He assembled an art collection that included fine French Impressionist works by Manet, Monet, Renoir and Sisley, as well as masterpieces of Realism and Post-Impressionism by Cézanne and van Gogh. At the time he was ranked as an internationally famous collector alongside Andrew Mellon, Jakob Goldschmidt and Mortimer Schiff. So naturally his treasures were requested for exhibitions around the world. As late as 1933, Max Silberberg's paintings were generously loaned for shows in Vienna and New York.

Silberberg, who was forced by the Nazis to dispose of the work in a Berlin sale in 1935, was exterminated in Auschwitz with his wife. In 1999, Max’s daughter in law Gerta Silberberg became the first British relative of a Holocaust victim to recover a work of art under the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-looted art. In 2000 the small painting was placed on loan with the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

artdaily noted that Camille Pissarro’s series paintings of Paris were among the supreme achievements of Impressionism, taking their place alongside Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral. Pissarro worked methodically for over two months on his Boulevard Montmartre series and held this particular painting in especially high esteem, writing to his dealer Durand-Ruel, ‘I have just received an invitation from the Carnegie Institute for this year’s exhibition: I’ve decided to send them the painting Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps… So please do not sell it’.

Pissarro’s paintings of Paris executed in the last years of the 1890s were hugely significant achievements that brilliantly evoke the excitement and spectacle of the city at the fin-de-siècle. For an artist who throughout his earlier career was primarily celebrated as a painter of rural life rather than the urban environment, the Boulevard Montmartre series was among a small group that confirmed his position as the preeminent painter of the city. Pissarro was able to exploit the artistic possibilities presented by the new urban landscape of Paris that Baron Haussmann’s renovations to the city had created.

The art market agreed. In February 2014 the Pissarro painting was auctioned at Sotheby's in London, and sold for £19,682,500, double its pre-sale estimate and five times the previous record for this particular Impressionist.

Although this post is just about the Pissarro painting of Montmartre, I did wonder what happened to the other 143 works of art from the Silberberg collection that were sold by the Nazis in four separate auctions between 1933 and 1938. The Foundation for Prussian Cultural Heritage, the organisation responsible for German museums, approved the return of a Vincent van Gogh and a Hans von Marees when its president asked for special authorisation to restore property to the children of people who died in the Holocaust. In 1999 the Foundation was successful, avoiding protracted and painful court proceedings, at least for two of the 143 art objects. Van Gogh’s Olive groces with Les Alpilles in the background was restituted to Gerta Silberberg from the National Gallery of Berlin in 1999.

The Bridge of Trinquetaille, 1888

by Vincent van Gogh.Was owned by Max Silberberg. Where is it now?