Arts Centre Melbourne

Felix Bischofswerder (1922-2012) was born in Berlin. He received his first music lessons from his father, the Jewish cantor Boas Bischofswerder in a leading Berlin synagogue. Felix's German heritage also greatly impacted his music. His father had also been a composer in Schoenberg's musical circle, and from primary school Felix had acted as copyist for his father. Synagogue music appeared in his use of the Hebraic modes in early works. This conveyed to him the spiritual and musical traditions of Judaism, including the worlds of Moses Mendelssohn and Arnold Schönberg.

After the Nazis took power, the family escaped to London in 1933 where his father again worked as a cantor. Felix finished high school, studied architecture and art history, then attended the Guildhall School of Music. In June 1940 he was arrested as an Enemy Alien and interned, then accompanied his father who was deported to Australia on the ship Dunera. While his father sickened from the miserable conditions aboard and in the Australian internment camps Hay and Tatura, Felix contributed to the musical life of the internees by writing works by George Frideric Handel and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart known for the camp orchestra from memory. Through style copies, he worked his way self-taught to his own compositions. The two years in the Tatura camp, where he also wrote a treatise on the history of Jewish music, he later called his most important school.

Felix was 18 when he was confined on the Dunera in 1940, so his fine works, including his symphonies, chamber music, choral works and operas, were all written in Australia.

In order to support his sick father financially, Felix volunteered for the Australian Army in 1943. Whilst in the army, he married Mena Waten, sister of novelist Judah Waten, who encouraged him in his leftist politics. Judah and Mena were my mother’s first cousins, so my musically skilled mother warmly welcomed Felix into the family.

When his father died in 1946, Felix ended his military service and received Australian citizenship as Werder. Although another musical refugee Werner Baer arranged for him to work as a music arranger, Felix had to take up a teacher training course in Melbourne in 1947 to gain a reliable income. He earned his living as an adult education teacher, and as choirmaster of the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation.

Public recognition and performance were at first hesitant; Werder’s orchestral Balletomania (1940) had to wait 8 years for its first performance. Violinist Szymon Goldberg, then living in Sydney, sent Werder’s music to the conductor Eugene Goossens, who then performed Balletomania in Oct 1948 with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Encouraged by Goosens and fellow-conductor Walter Susskind, Werder had the support of the concert organisation Musica Viva Australia, founded in 1945 by Richard Goldner, a Jewish Viennese-trained violist refugee. It became the world's largest entrepreneurial chamber music organisation.

Kisses for a Quid by Felix Werder

After the Nazis took power, the family escaped to London in 1933 where his father again worked as a cantor. Felix finished high school, studied architecture and art history, then attended the Guildhall School of Music. In June 1940 he was arrested as an Enemy Alien and interned, then accompanied his father who was deported to Australia on the ship Dunera. While his father sickened from the miserable conditions aboard and in the Australian internment camps Hay and Tatura, Felix contributed to the musical life of the internees by writing works by George Frideric Handel and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart known for the camp orchestra from memory. Through style copies, he worked his way self-taught to his own compositions. The two years in the Tatura camp, where he also wrote a treatise on the history of Jewish music, he later called his most important school.

Felix was 18 when he was confined on the Dunera in 1940, so his fine works, including his symphonies, chamber music, choral works and operas, were all written in Australia.

In order to support his sick father financially, Felix volunteered for the Australian Army in 1943. Whilst in the army, he married Mena Waten, sister of novelist Judah Waten, who encouraged him in his leftist politics. Judah and Mena were my mother’s first cousins, so my musically skilled mother warmly welcomed Felix into the family.

When his father died in 1946, Felix ended his military service and received Australian citizenship as Werder. Although another musical refugee Werner Baer arranged for him to work as a music arranger, Felix had to take up a teacher training course in Melbourne in 1947 to gain a reliable income. He earned his living as an adult education teacher, and as choirmaster of the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation.

Public recognition and performance were at first hesitant; Werder’s orchestral Balletomania (1940) had to wait 8 years for its first performance. Violinist Szymon Goldberg, then living in Sydney, sent Werder’s music to the conductor Eugene Goossens, who then performed Balletomania in Oct 1948 with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Encouraged by Goosens and fellow-conductor Walter Susskind, Werder had the support of the concert organisation Musica Viva Australia, founded in 1945 by Richard Goldner, a Jewish Viennese-trained violist refugee. It became the world's largest entrepreneurial chamber music organisation.

Q Theatre Guild, 1961

Victorian Collections

Werder's influence grew considerably when he became music critic of the top newspaper The Age in Melbourne in 1960. His criticism, taking European culture as a baseline, earned him as much respect as disagreement. Werder was a leading figure in the Australian avant-garde, but has always attached great importance to his European roots. His extensive catalogue of works ranged from chamber, choral and orchestral music to 8 operas.

In 1965 Sydney Symphony Orchestra performed Elegy for Strings at the Royal Festival Hall in London, then Fritz Rieger performed Violin Concerto (1966) in Melbourne. Only by the late 1970s was Werder's influence declining, even though he still gathered a crowd of keen students around him.

He could no longer go on major journeys after a stroke in 2000, but remained active as a composer until the end. In 2003-4 Albrecht Duemling used the National Library of Australia’s music collection to document both the personal experiences of refugee musicians and their professional contributions to Australian music. In his new book The Vanished Musicians: Jewish refugees in Australia 2011, he discussed the reception Australia offered to German-speaking refugee musicians who arrived here from 1933 on.

In Feb 2012, his 19th string quartet, The H-Factor, was premiered at a concert for his 90th birthday. Felix Werder died in 2012 in Melbourne.

c9,000 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany settled in Australia during 1933-45. Australia should have felt blessed when world-famous Jewish musicians arrived on our shores. Consider piano virtuoso Jascha Spivakovsky and his trio (with Nathan Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz), Artur Schnabel, Richard Tauber and Yehudi Menuhin, and the conductor Maurice Abravanel. The composer and basoonist George Dreyfus was even younger when he left Germany in 1938, so he did all his musical studies in Australia. How tragic that these Jewish refugees, fleeing Nazism at home, were declared enemy-alien-Germans in Australia. Most were imprisoned in rural camps, in Hay and Tatura.

So the modern viewer asks if the Musicians’ Union of Australia tried to save these professional musicians and composers in the late 1930s. Apparently not. The Musicians’ Union felt it was hard enough to find full-time work for real Australian citizens and applied pressure on the Immigration Department to turn foreign musicians away from our shores or put them in non-musical jobs. If a talented musician wanted Australian citizenship in 1939, he was advised call himself a factory worker or shoe maker ☹ Most did.

In 1965 Sydney Symphony Orchestra performed Elegy for Strings at the Royal Festival Hall in London, then Fritz Rieger performed Violin Concerto (1966) in Melbourne. Only by the late 1970s was Werder's influence declining, even though he still gathered a crowd of keen students around him.

He could no longer go on major journeys after a stroke in 2000, but remained active as a composer until the end. In 2003-4 Albrecht Duemling used the National Library of Australia’s music collection to document both the personal experiences of refugee musicians and their professional contributions to Australian music. In his new book The Vanished Musicians: Jewish refugees in Australia 2011, he discussed the reception Australia offered to German-speaking refugee musicians who arrived here from 1933 on.

In Feb 2012, his 19th string quartet, The H-Factor, was premiered at a concert for his 90th birthday. Felix Werder died in 2012 in Melbourne.

c9,000 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany settled in Australia during 1933-45. Australia should have felt blessed when world-famous Jewish musicians arrived on our shores. Consider piano virtuoso Jascha Spivakovsky and his trio (with Nathan Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz), Artur Schnabel, Richard Tauber and Yehudi Menuhin, and the conductor Maurice Abravanel. The composer and basoonist George Dreyfus was even younger when he left Germany in 1938, so he did all his musical studies in Australia. How tragic that these Jewish refugees, fleeing Nazism at home, were declared enemy-alien-Germans in Australia. Most were imprisoned in rural camps, in Hay and Tatura.

So the modern viewer asks if the Musicians’ Union of Australia tried to save these professional musicians and composers in the late 1930s. Apparently not. The Musicians’ Union felt it was hard enough to find full-time work for real Australian citizens and applied pressure on the Immigration Department to turn foreign musicians away from our shores or put them in non-musical jobs. If a talented musician wanted Australian citizenship in 1939, he was advised call himself a factory worker or shoe maker ☹ Most did.

Discogs, 1969

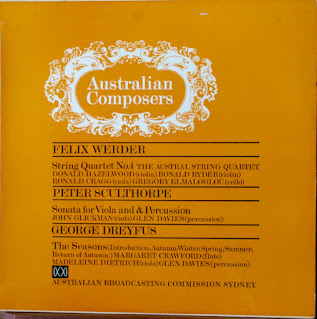

Australian Composers

Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1970

Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1970

Discogs

Conclusion

The refugees were initially received as Enemy Aliens but many of them remained here and made a significant impact on multicultural Australia. Albrecht Duemling's book The Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia traced the difficult journey of 100 displaced orchestral performers, conductors and composers who’d sought refuge from Nazism. See Werder’s and others’ biographies in Duemling’s book.

The Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia

by Albrecht Dümling, 2016

by Albrecht Dümling, 2016

Amazon