The Arts Club was founded in 1863 to provide a haven for people who had professional or non-professional links to the Arts, Literature or Sciences. According to the club’s own home page, a small group of friends including Dickens and Trollope got together and drew in new members like Tennyson, Monet, Manet, Rodin and Winston Churchill soon after. In 1896, the Club relocated from its original home on Hanover Square to its present elegant C18th townhouse at 40 Dover St, offering its members a comfortable, arty and impressive base in Mayfair. In the basement, there is a live music club room and there is a contemporary art collection that looks like a professional gallery.

Since then, the Club gave membership to many outstanding figures in the history of art, literature and science: writers like Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins; musicians like Franz Liszt; and artists Frederic Leighton, Walter Sickert, John Everett Millais, Auguste Rodin and James McNeill Whistler, as well as famous professionals. The Arts Club survived two world wars, despite a direct hit during the 1940 Blitz.

In Sep 2011, the Arts Club was renovated and re-launched. The current members are involved in art, architecture, fashion, film, music, literature, performance, photography, science and theatre. It proudly continues to be a hub for creative and entrepreneurial patrons to come together to dine and participate in the events; thus the Club has reclaimed its central place in London’s modern cultural life.

Since then, the Club gave membership to many outstanding figures in the history of art, literature and science: writers like Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins; musicians like Franz Liszt; and artists Frederic Leighton, Walter Sickert, John Everett Millais, Auguste Rodin and James McNeill Whistler, as well as famous professionals. The Arts Club survived two world wars, despite a direct hit during the 1940 Blitz.

In Sep 2011, the Arts Club was renovated and re-launched. The current members are involved in art, architecture, fashion, film, music, literature, performance, photography, science and theatre. It proudly continues to be a hub for creative and entrepreneurial patrons to come together to dine and participate in the events; thus the Club has reclaimed its central place in London’s modern cultural life.

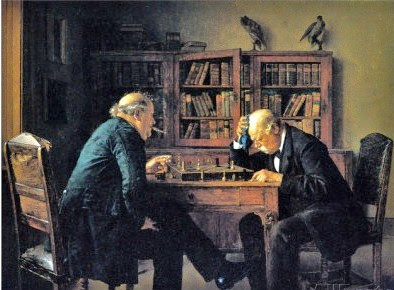

The Arts Club drawing room

The Arts Club’s collection includes the permanent display of works by three modern artists, alongside the Club's historic collection of British/international artists and temporary exhibitions. And to show that there is more to the Arts Club than drinking oneself to a standstill, there are regular lectures and recitals.

London’s other private members’ clubs continued with expansion. After WW2, clubs were still filled with the arts, but had to be louder, more hip and more sexy. Annabel's was founded in 1963 by entrepreneur Mark Birley, the very educated son of the artist Sir Oswald Birley, favourite portrait painter of the royal family. Mark Birley had worked for Hermes, the luxury goods maker. When his friend John Aspinall turned a large Palladian house into the Clermont Club Casino, he offered Birley the lease on the basement. Apparently they needed somewhere to party, after an evening's gambling.

Birley turned the basement of the Clermont Club Casino into a nightclub and blocked off the private staircase going up into the Clermont above. Since 1963, this intimate Berkeley Square basement has attracted a gilded, glittering clientele and aristocrats. Named after Birley’s glamorous wife, now Lady Annabel Goldsmith, the club proudly declared it was a safe haven from journalists.

Parts of this elegant and exclusive Mayfair site had a sumptuous interior: vaulted Moorish ceiling, pillars covered with antiqued brass and outstanding collection of objets d’art. Each year there was a week of fashion shows, devised by the later fashion designer Alexander McQueen.

Pavel Tchelitchew was the Russian-born surrealist painter, set designer and costume designer. Tchelitchew was born to a noble landed family, a man who left Russia for Berlin and then Paris in the 1920. Tchelitchew’s watercolours were perfect for two reasons. Firstly Birley was fascinated with Russian ballet. And secondly Tchelitchew was close with Gertrude Stein and the Sitwells.

Posh yes, but Birley wanted to create some space that had the feel of an English country house. The room and bars and the little nooks were furnished with comfortable sofas, a large Buddha, soft armchairs and a wide range of art: oil paintings of Birley’s dogs next to works by Augustus John.

Against this contemporary club backdrop, some of the older clubs in London that once serviced the wealthy and the glamorous have been getting a bit dusty, banking on exclusivity. Even Annabel’s also had another look at itself. In June 2007, after more than a year of negotiations, the clothing businessman/Ivy Restaurant owner Richard Caring bought Mark Birley’s valuable trio of Mayfair hangouts – Annabel’s, Harry’s Bar and Mark’s Club.

Annabel's could now modernise, largely thanks to Guillaume Glipa, executive director of The Birley Group. Annabel’s was moved to a spectacular Grade I-listed Georgian townhouse at 46 Berkeley Square, just two doors from its current site in Berkeley Square. The new club was designed by Martin Brudnizki, who was also responsible for the makeover of The Ivy.

The new Annabel's has taken over 4 floors and will be offering three restaurants, two private dining rooms, six bars and a nightclub in the basement. New designs for the club include a £4 million retractable glass roof over a hidden garden-dining terrace behind Berkeley Square seating 100 people. There will be a barber’s in the men’s room, with mother-of-pearl doors, a cigar shop and a wine shop. The 1963 club and restaurant is being turned into a health and wellbeing spa. The day club will be open from 7am to 4am.

The Evening Standard has been inside. Annabel’s commissioned the best craftsmen, designers and artisans to use the most beautiful colours, textiles, materials and objects. The original Nina Campbell interiors have been updated for the C21st, while retaining Annabel’s trademark dusky mood. Note the hand-pleated crimson silk walling fabric and paisley-print carpets in the Indian Room.

When this smart townhouse venue re-opens in Nov 2017, Berkeley Square will never have been so hot.

London’s other private members’ clubs continued with expansion. After WW2, clubs were still filled with the arts, but had to be louder, more hip and more sexy. Annabel's was founded in 1963 by entrepreneur Mark Birley, the very educated son of the artist Sir Oswald Birley, favourite portrait painter of the royal family. Mark Birley had worked for Hermes, the luxury goods maker. When his friend John Aspinall turned a large Palladian house into the Clermont Club Casino, he offered Birley the lease on the basement. Apparently they needed somewhere to party, after an evening's gambling.

Birley turned the basement of the Clermont Club Casino into a nightclub and blocked off the private staircase going up into the Clermont above. Since 1963, this intimate Berkeley Square basement has attracted a gilded, glittering clientele and aristocrats. Named after Birley’s glamorous wife, now Lady Annabel Goldsmith, the club proudly declared it was a safe haven from journalists.

Parts of this elegant and exclusive Mayfair site had a sumptuous interior: vaulted Moorish ceiling, pillars covered with antiqued brass and outstanding collection of objets d’art. Each year there was a week of fashion shows, devised by the later fashion designer Alexander McQueen.

Pavel Tchelitchew was the Russian-born surrealist painter, set designer and costume designer. Tchelitchew was born to a noble landed family, a man who left Russia for Berlin and then Paris in the 1920. Tchelitchew’s watercolours were perfect for two reasons. Firstly Birley was fascinated with Russian ballet. And secondly Tchelitchew was close with Gertrude Stein and the Sitwells.

Posh yes, but Birley wanted to create some space that had the feel of an English country house. The room and bars and the little nooks were furnished with comfortable sofas, a large Buddha, soft armchairs and a wide range of art: oil paintings of Birley’s dogs next to works by Augustus John.

Against this contemporary club backdrop, some of the older clubs in London that once serviced the wealthy and the glamorous have been getting a bit dusty, banking on exclusivity. Even Annabel’s also had another look at itself. In June 2007, after more than a year of negotiations, the clothing businessman/Ivy Restaurant owner Richard Caring bought Mark Birley’s valuable trio of Mayfair hangouts – Annabel’s, Harry’s Bar and Mark’s Club.

Annabel's could now modernise, largely thanks to Guillaume Glipa, executive director of The Birley Group. Annabel’s was moved to a spectacular Grade I-listed Georgian townhouse at 46 Berkeley Square, just two doors from its current site in Berkeley Square. The new club was designed by Martin Brudnizki, who was also responsible for the makeover of The Ivy.

The new Annabel's has taken over 4 floors and will be offering three restaurants, two private dining rooms, six bars and a nightclub in the basement. New designs for the club include a £4 million retractable glass roof over a hidden garden-dining terrace behind Berkeley Square seating 100 people. There will be a barber’s in the men’s room, with mother-of-pearl doors, a cigar shop and a wine shop. The 1963 club and restaurant is being turned into a health and wellbeing spa. The day club will be open from 7am to 4am.

Annabel's dining room

Annabel's mirrored room in the basement

A bar at Annabel's

When this smart townhouse venue re-opens in Nov 2017, Berkeley Square will never have been so hot.