Edith Newbold Jones (b1862) grew up in a privileged Massachusetts society that barred women from achieving anything other than a suitable marriage. Her education was limited since she never went to a proper school or university, and her mother maintained a strict literary censorship over Edith’s reading. Yet this woman of the Gilded Age (Civil War-WW1) travelled to Europe many times and became fluent in three European languages.

Because Edith wasn’t pretty, getting married wasn’t going to be easy. Nonetheless in 1885 she married Edward Wharton. Despite Teddy being an affable dud of modest means and a man who was displaying early symptoms of mental illness, the couple filled their early years with travel, houses and dogs (but no sex).

Edith Wharton

Because Edith wasn’t pretty, getting married wasn’t going to be easy. Nonetheless in 1885 she married Edward Wharton. Despite Teddy being an affable dud of modest means and a man who was displaying early symptoms of mental illness, the couple filled their early years with travel, houses and dogs (but no sex).

Edith Wharton

The Whartons purchased The Mount estatein West Ma in 1902 from Georgiana Sargent, artist-cousin of painter John Singer Sargent. Edith’s mother had just died, and the chief executor (her brother) ensured mother’s will would never be divided equally. Wharton hadn’t yet reached the height of her fame at the time and her funds were very tight, so I wonder who paid for the 113 original acres

The Berkshires worked as a place where wealthy families relaxed each summer. A separate and poorer community of writers and artists also lived in Lenox, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Herman Melville.

Writing years earlier in the Newport Daily News about Georgian style, Wharton had noted that in America “the Georgian house does not affect to be a castle, a fortress or a farmhouse ...it possesses the important merit of affording more space, light and comfort for a given price than any other structure with the slightest architectural pretensions”.

Wharton had outlined her house design according to the principles in her book The Decoration of Houses (1897). The house and gardens were an integral part of her life and she was proud of her achievements. “The core of my life was under my roof, among my books and my intimate friends ... I am amazed at the success of my efforts. Decidedly, I’m a better landscape gardener than novelist.

The exterior architects that Edith chose, Hoppin & Koen, used the Georgian-style Belton House (1684-1686) in the British county of Lincolnshire as a model for The Mount.

The Mount, with its 35 rooms, four floors and formal gardens, was said to be a tad modest for a Gilded Age home!! So Wharton hired her friend Ogden Codman to do the building’s Italian and French interiors. This was appropriate since Codman was both a practising architect-interior decorator AND he had co-authored her The Décoration of Houses book. But he did not get along with the increasingly psychotic Teddy Wharton.

Wharton usually worked in the morning while lying in bed.. so her bedroom was an important space. Visitors can still enjoy afternoon tea on the expansive terrace, an Italian element requested by Wharton. Then visitors enter the wood-panelled library where Edith worked in the afternoon. Her closest cultural friends – Sinclair Lewis, Henry James, Bernard Berenson and F Scott Fitzgerald– met her in this library. Her literary hero was Walt Whitman and the library still holds her annotated copies of his poetry books.

Though the marriage eventually fell apart, the house succeeded - it helped her work. While living there Wharton wrote a book a year, including the big novel that would launch her into fame and wealth, The House of Mirth 1905. In it Lily Bart was a well-bred woman without money in New York’s fin de siècle high society. Wharton wrote of a stunning beauty who, though raised and educated to marry well, was running out of marrying years.

Edith also wrote the following novels while living at the Mount: The Touchstone 1900; The Valley of Decision 1902; Sanctuary 1903; Madame de Treymes, 1906; The Fruit of the Tree 1907 and Ethan Frome 1911. She also wrote at least three important works of non-fiction: Italian Villas and Their Gardens, 1904; Italian Backgrounds, 1905 and A Motor-Flight Through France, 1908.

So The Mount sustained Edith in that important and creative period, until Teddy’s mental instability led to divorce. She sold the estate in 1911 and the couple divorced two years later. Teddy moved in with his sister in a different Lenox house and Edith moved permanently to France. “It was only at the Mount that I was really happy,” she later wrote in her memoir, A Backward Glance.

Foxhollow School for Girls, which took over The Mount, closed down in 1976. For the next two decades, the property was taken over by Edith Wharton Restoration, used as the home of Shakespeare & Co.

The Mount became a National Historic Landmark; and it also became an autobiographical house that specifically embodied the soul of its creator. Now the Mount is available to anyone who wants to drive across New England to Lenox. And so far 40,000+ people have visited this year, following the tours listed. Additionally the Mount invited theatre companies, prominent writers and intellectuals to come and give lectures to sold-out auditoriums. Clearly there was a great hunger for intellectual content in Lenox.

Edith Wharton wrote 40+ books throughout her career, including important works on interior design, architecture and gardens. She was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921 and she achieved full membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1926. She died in France in 1937 and was buried in the Protestant cemetery at Versailles.

Thank you Edith. You were one of my role models from the world of English literature written by women.

The Berkshires worked as a place where wealthy families relaxed each summer. A separate and poorer community of writers and artists also lived in Lenox, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Herman Melville.

Writing years earlier in the Newport Daily News about Georgian style, Wharton had noted that in America “the Georgian house does not affect to be a castle, a fortress or a farmhouse ...it possesses the important merit of affording more space, light and comfort for a given price than any other structure with the slightest architectural pretensions”.

Wharton had outlined her house design according to the principles in her book The Decoration of Houses (1897). The house and gardens were an integral part of her life and she was proud of her achievements. “The core of my life was under my roof, among my books and my intimate friends ... I am amazed at the success of my efforts. Decidedly, I’m a better landscape gardener than novelist.

The exterior architects that Edith chose, Hoppin & Koen, used the Georgian-style Belton House (1684-1686) in the British county of Lincolnshire as a model for The Mount.

The Mount, with its 35 rooms, four floors and formal gardens, was said to be a tad modest for a Gilded Age home!! So Wharton hired her friend Ogden Codman to do the building’s Italian and French interiors. This was appropriate since Codman was both a practising architect-interior decorator AND he had co-authored her The Décoration of Houses book. But he did not get along with the increasingly psychotic Teddy Wharton.

Wharton usually worked in the morning while lying in bed.. so her bedroom was an important space. Visitors can still enjoy afternoon tea on the expansive terrace, an Italian element requested by Wharton. Then visitors enter the wood-panelled library where Edith worked in the afternoon. Her closest cultural friends – Sinclair Lewis, Henry James, Bernard Berenson and F Scott Fitzgerald– met her in this library. Her literary hero was Walt Whitman and the library still holds her annotated copies of his poetry books.

Though the marriage eventually fell apart, the house succeeded - it helped her work. While living there Wharton wrote a book a year, including the big novel that would launch her into fame and wealth, The House of Mirth 1905. In it Lily Bart was a well-bred woman without money in New York’s fin de siècle high society. Wharton wrote of a stunning beauty who, though raised and educated to marry well, was running out of marrying years.

Edith also wrote the following novels while living at the Mount: The Touchstone 1900; The Valley of Decision 1902; Sanctuary 1903; Madame de Treymes, 1906; The Fruit of the Tree 1907 and Ethan Frome 1911. She also wrote at least three important works of non-fiction: Italian Villas and Their Gardens, 1904; Italian Backgrounds, 1905 and A Motor-Flight Through France, 1908.

So The Mount sustained Edith in that important and creative period, until Teddy’s mental instability led to divorce. She sold the estate in 1911 and the couple divorced two years later. Teddy moved in with his sister in a different Lenox house and Edith moved permanently to France. “It was only at the Mount that I was really happy,” she later wrote in her memoir, A Backward Glance.

Foxhollow School for Girls, which took over The Mount, closed down in 1976. For the next two decades, the property was taken over by Edith Wharton Restoration, used as the home of Shakespeare & Co.

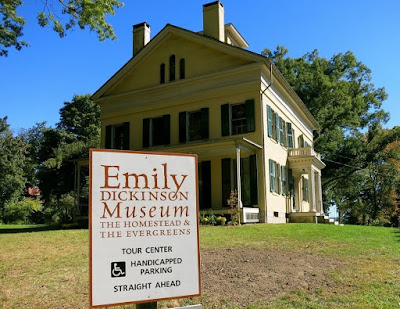

The Mount and its gardens, in Lenox, Ma

Edith Wharton's library, The Mount

Restoration of the estate did not begin until 1997. After years of hard use and little maintenance, the buildings were falling apart and the gardens were overgrown. In 2008 the Mount’s debt stood at $8.5m, owed to the bank that was threatening to foreclose on the house. A public Save the Mount campaign was urgently required. Eventually the Mount raised enough money to pay off its entire debt. Thankfully the $2.6m purchase of a collection of books Wharton had once owned herself, while exorbitant, brought her books back home.

The Mount became a National Historic Landmark; and it also became an autobiographical house that specifically embodied the soul of its creator. Now the Mount is available to anyone who wants to drive across New England to Lenox. And so far 40,000+ people have visited this year, following the tours listed. Additionally the Mount invited theatre companies, prominent writers and intellectuals to come and give lectures to sold-out auditoriums. Clearly there was a great hunger for intellectual content in Lenox.

Edith Wharton wrote 40+ books throughout her career, including important works on interior design, architecture and gardens. She was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921 and she achieved full membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1926. She died in France in 1937 and was buried in the Protestant cemetery at Versailles.

Thank you Edith. You were one of my role models from the world of English literature written by women.