English Catholics had endured religious discrimination since 1570, when the Pope had excommunicated Queen Elizabeth, releasing her subjects from allegiance to her. Even worse for Catholics, the Spanish Armada of 1588 confirmed to the Tudors that all Catholics were potential traitors. Catholic recusants were steeply fined, or worse.

So 1603 was going to be an important turning point. After 45 years on the English throne, Protestant Queen Elizabeth I seemed to be about to name King James VI of Scotland to succeed her as King of England. Despite his mother, the executed Mary Queen of Scots, being Catholic, James had been raised as a Protestant. So why did he marry a Catholic, Queen Anne of Denmark? The secretly-Catholic Earl of Northumberland sent one of his staff to Scotland, to assess how English Catholics might fare under the new king.

Certainly the new king did end the hated recusancy fines and did give important posts to the Earl of Northumberland. English Catholics breathed a sigh of relief. But not for long. Rather than tolerate a new era of religious tolerance, the bitterly disappointed Catholics decided to take action.

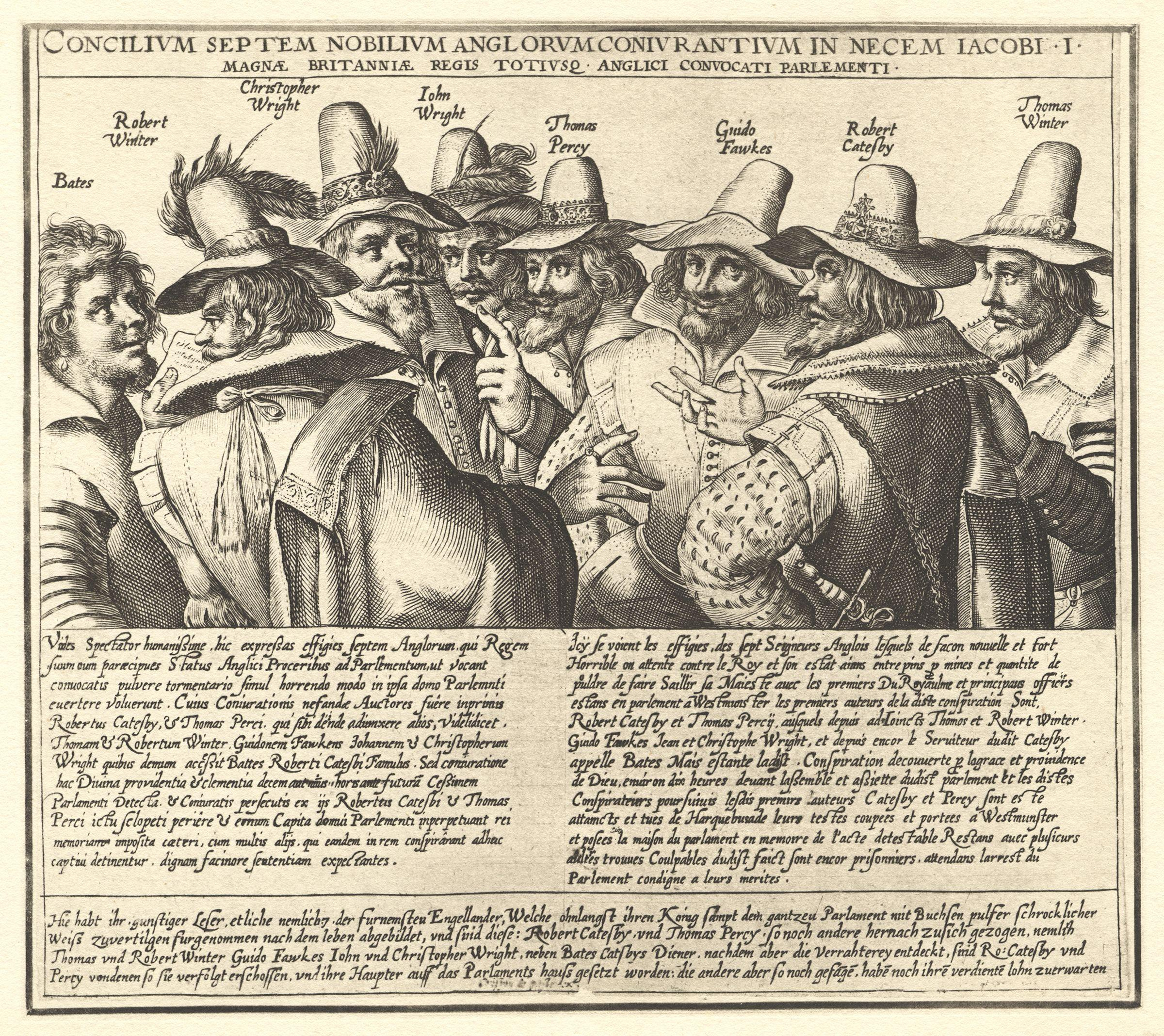

Some plotters from the Midlands got together in mid 1604. Robert Catesby, Thomas Wintour, Jack Wright, Thomas Percy and Guy Fawkes met in a London pub. Fawkes had been recruited in Flanders, where he had been serving honourably in the Spanish Army, as he was an expert on gunpowder. They discussed their plan to blow up Parliament House, and shortly afterwards leased a small house in the heart of Westminster, installing Fawkes (with a fake name) as a servant to Thomas Percy.

Catesby recruited Ambrose Rookwood, Francis Tresham and Sir Everard Digby. Both Rookwood and Digby were wealthy and owned large numbers of horses, essential for the plan. Tresham was Catesby's cousin through marriage, and was brother-in-law to two Catholic peers, Lords Stourton and Monteagle. Eventually there were 13 plotters.

With Parliament due to open on 5th November 1605, the plotters had to collect and install 36 barrels of gunpowder below the House of Lords, intending to blow up King James and all the Parliamentarians when the king opened the new session. So why did it go so terribly wrong?

Apparently English spies reported back to King James' first minister Robert Cecil Earl of Salisbury, and made the link between Fawkes and Catesby. According to Neil Jones, the government could have intervened at that stage, but they bided their time to get propaganda value for the great “discovery” on the day of the intended explosion.

Fawkes was to light the fuse and escape to continental Europe. To coincide with the explosion, Digby planned to lead a rising in the Midlands and kidnap King James's daughter, to install her as a puppet queen. In Catholic Europe, Fawkes was to argue the plotters' case to various governments, hopefully to secure their support.

Everything seemed ready. But at the end of October, an anonymous letter was delivered to the Catholic Lord Monteagle, suggesting that he stay away from the Parliament’s opening day. Who sent it? Neil Jones suggested two possibilities: a] that one of the plotters, Monteagle’s brother in law Francis Tresham, was actually a Stuart spy and b] that the letter was a fake, written by the king’s main minister to set up the plotters for certain failure. In either case, the letter should have been a clue to the plotters, but they went ahead with their plans. Catesby, Wright and Bates set off for the Midlands, unperturbed.

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl Salisbury ordered Westminster to be searched. The search found Fawkes and his gunpowder underground, so the plotter was immediately arrested. The other plotters escaped from London for the Midlands, as quickly as they could.

In the Midlands, the plotters raided Warwick Castle. But the end came quickly when the local High Sheriff rode in with his soldiers and killed Catesby, the Wrights and Percy; and captured Thomas Wintour, Rookwood and Grant. Under torture the survivors implicated the Jesuits in the gunpowder plot, and ordinary Catholic homes everywhere were subject to destruction.

In late January 1606 the trials began, and naturally Westminster Hall was packed out. Under instructions from Earl Salisbury, the Attorney General laid the blame squarely on the Jesuits, before ordering the punishment for traitors: they’d be hanged, drawn and quartered. Their body parts would be publicly displayed.

All were found guilty of high treason. Digby, Robert Wintour, Bates and Grant were executed in Jan, with Thomas Wintour, Rookwood, Keyes and Fawkes soon after. Only Tresham was spared a trial and a hideous execution, leading Neil Jones to again suspect that Tresham was indeed a double agent. Percy, the Earl of Northumberland was imprisoned in the Tower until 1621.

Every Catholic in the nation felt the wrath of Parliament and the distrust of their Protestant neighbours. New laws were passed preventing them from voting, and from working in the most sensitive professions: the law and the armed services. They paid a hefty price throughout the remainder of the 17th century, including perhaps in the abdication/expulsion of King James II in 1688.

In the meantime, 5th of November became a night of thanksgiving in churches, sermons, fireworks and throwing the “guy” (an effigy of Guy Fawkes) onto bonfires throughout Protestant Britain every year, and thence to colonies across the British Empire. Throwing the guy on the bonfire was the yearly highlight of my entire childhood, even though Guy Fawkes didn't devise or lead the plot to assassinate King James I.

So 1603 was going to be an important turning point. After 45 years on the English throne, Protestant Queen Elizabeth I seemed to be about to name King James VI of Scotland to succeed her as King of England. Despite his mother, the executed Mary Queen of Scots, being Catholic, James had been raised as a Protestant. So why did he marry a Catholic, Queen Anne of Denmark? The secretly-Catholic Earl of Northumberland sent one of his staff to Scotland, to assess how English Catholics might fare under the new king.

Certainly the new king did end the hated recusancy fines and did give important posts to the Earl of Northumberland. English Catholics breathed a sigh of relief. But not for long. Rather than tolerate a new era of religious tolerance, the bitterly disappointed Catholics decided to take action.

Participants in the Gunpowder Plot to blow up Parliament and to kill King James I

November 1605

Catesby recruited Ambrose Rookwood, Francis Tresham and Sir Everard Digby. Both Rookwood and Digby were wealthy and owned large numbers of horses, essential for the plan. Tresham was Catesby's cousin through marriage, and was brother-in-law to two Catholic peers, Lords Stourton and Monteagle. Eventually there were 13 plotters.

With Parliament due to open on 5th November 1605, the plotters had to collect and install 36 barrels of gunpowder below the House of Lords, intending to blow up King James and all the Parliamentarians when the king opened the new session. So why did it go so terribly wrong?

Apparently English spies reported back to King James' first minister Robert Cecil Earl of Salisbury, and made the link between Fawkes and Catesby. According to Neil Jones, the government could have intervened at that stage, but they bided their time to get propaganda value for the great “discovery” on the day of the intended explosion.

Fawkes was to light the fuse and escape to continental Europe. To coincide with the explosion, Digby planned to lead a rising in the Midlands and kidnap King James's daughter, to install her as a puppet queen. In Catholic Europe, Fawkes was to argue the plotters' case to various governments, hopefully to secure their support.

Everything seemed ready. But at the end of October, an anonymous letter was delivered to the Catholic Lord Monteagle, suggesting that he stay away from the Parliament’s opening day. Who sent it? Neil Jones suggested two possibilities: a] that one of the plotters, Monteagle’s brother in law Francis Tresham, was actually a Stuart spy and b] that the letter was a fake, written by the king’s main minister to set up the plotters for certain failure. In either case, the letter should have been a clue to the plotters, but they went ahead with their plans. Catesby, Wright and Bates set off for the Midlands, unperturbed.

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl Salisbury ordered Westminster to be searched. The search found Fawkes and his gunpowder underground, so the plotter was immediately arrested. The other plotters escaped from London for the Midlands, as quickly as they could.

In the Midlands, the plotters raided Warwick Castle. But the end came quickly when the local High Sheriff rode in with his soldiers and killed Catesby, the Wrights and Percy; and captured Thomas Wintour, Rookwood and Grant. Under torture the survivors implicated the Jesuits in the gunpowder plot, and ordinary Catholic homes everywhere were subject to destruction.

In late January 1606 the trials began, and naturally Westminster Hall was packed out. Under instructions from Earl Salisbury, the Attorney General laid the blame squarely on the Jesuits, before ordering the punishment for traitors: they’d be hanged, drawn and quartered. Their body parts would be publicly displayed.

Every Catholic in the nation felt the wrath of Parliament and the distrust of their Protestant neighbours. New laws were passed preventing them from voting, and from working in the most sensitive professions: the law and the armed services. They paid a hefty price throughout the remainder of the 17th century, including perhaps in the abdication/expulsion of King James II in 1688.

In the meantime, 5th of November became a night of thanksgiving in churches, sermons, fireworks and throwing the “guy” (an effigy of Guy Fawkes) onto bonfires throughout Protestant Britain every year, and thence to colonies across the British Empire. Throwing the guy on the bonfire was the yearly highlight of my entire childhood, even though Guy Fawkes didn't devise or lead the plot to assassinate King James I.